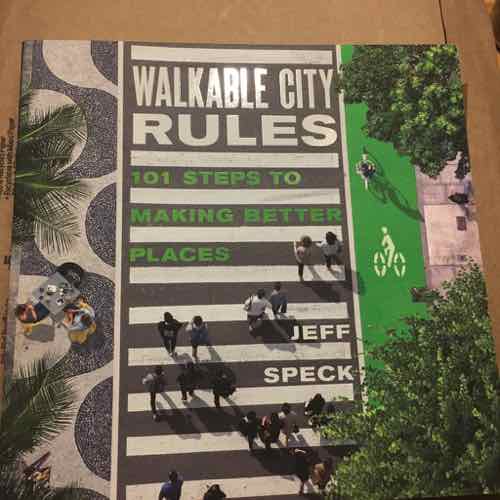

New Book — ‘Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places’ by Jeff Speck

I’m usually unbiased when publishers send me new books, but I’m a huge fan of Jeff Speck’s work as a New Urbanist planner. His latest book focuses on one of my favorite topics: walkability:

“Cities are the future of the human race, and Jeff Speck knows how to make them work.”

—David Owen, staff writer at the New YorkerNearly every US city would like to be more walkable—for reasons of health, wealth, and the environment—yet few are taking the proper steps to get there. The goals are often clear, but the path is seldom easy. Jeff Speck’s follow-up to his bestselling Walkable City is the resource that cities and citizens need to usher in an era of renewed street life. Walkable City Rules is a doer’s guide to making change in cities, and making it now.

The 101 rules are practical yet engaging—worded for arguments at the planning commission, illustrated for clarity, and packed with specifications as well as data. For ease of use, the rules are grouped into 19 chapters that cover everything from selling walkability, to getting the parking right, escaping automobilism, making comfortable spaces and interesting places, and doing it now!

Walkable City was written to inspire; Walkable City Rules was written to enable. It is the most comprehensive tool available for bringing the latest and most effective city-planning practices to bear in your community. The content and presentation make it a force multiplier for place-makers and change-makers everywhere. (Island Press)

He’s done two Ted Talks — back to back 5 years ago:

This newest book suggests 101 rules to make cities more walkable, organized in the following 19 sections:

- Sell Walkability

- Mix the Uses

- Make Housing Attainable and Integrated

- Get the Parking Right

- Let Transit Work

- Escape Automobilism

- Start with Safety

- Optimize Your Driving Network

- Right-Size the Number of Lanes

- Right-Size the Lanes

- Sell Cycling

- Build Your Bike Network

- Park On Street

- Focus on Geometry

- Focus on Intersections

- Make Sidewalks Right

- Make Comfortable Spaces

- Make Interesting Places

- Do It Now

Streetsblog has been posting full text of some of the rules:

- #26: Anticipate Autonomous Vehicles

- #51: Expand the Fire Chief’s Mandate

- #71: Remove Centerlines on Neighborhood Streets

- #76: Replace Signals with All-way Stops

Some of the rules of interest to me are:

- #6: Invest in Attainable Housing

- #14: Fight Displacement

- #20: Coordinate Transit and Land Use

- #37: Keep Blocks Small

- #75 Bag the Beg Buttons and Countdown Clocks

However, all are interesting. I’m planning to use the upcoming holidays to read through all 101 in detail.

You can see a preview at Google Books.

— Steve Patterson

Alleys are one thing that attracted me to St. Louis in 1990, we didn’t have them in the 1960s suburban subdivision where I grew up in Oklahoma City. Interestingly, my grandparents each had alleys behind their homes in the small Western Oklahoma towns of

Alleys are one thing that attracted me to St. Louis in 1990, we didn’t have them in the 1960s suburban subdivision where I grew up in Oklahoma City. Interestingly, my grandparents each had alleys behind their homes in the small Western Oklahoma towns of