Racially Restrictive Covenants Ruled Unenforceable 75 Years Ago Today

At the beginning of the 20th century racism was thriving, though it took different forms in different places. The south had harsh ”Jim Crow” laws, lynchings, etc. Cities like St. Louis were less overt, but were still very racially segregated.

In 1916, St. Louisans voted on a “reform” ordinance that would prevent anyone from buying a home in a neighborhood more than 75 percent occupied by another race. Civic leaders opposed the initiative, but it passed with a two-thirds majority and became the first referendum in the nation to impose racial segregation on housing. After a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Buchanan v. Warley, made the ordinance illegal the following year, some St. Louisans reverted to racial covenants, asking every family on a block or in a subdivision to sign a legal document promising to never sell to an African-American. Not until 1948 were such covenants made illegal, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Shelley v. Kraemer, a case originating in St. Louis.

— St. Louis Magazine

Here’s a summary of the two cases the U.S. Supreme Court consolidated, the namesake is from St. Louis.

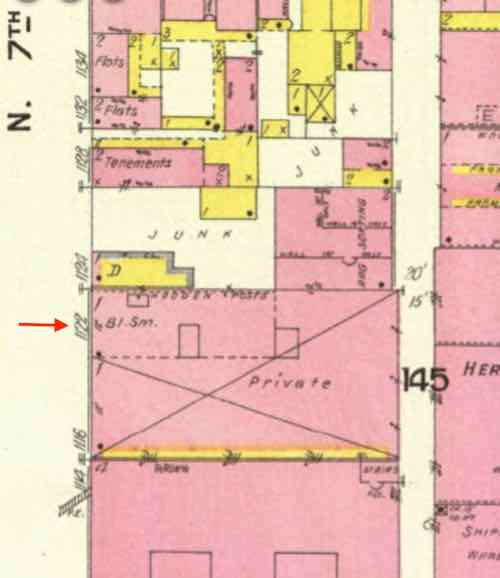

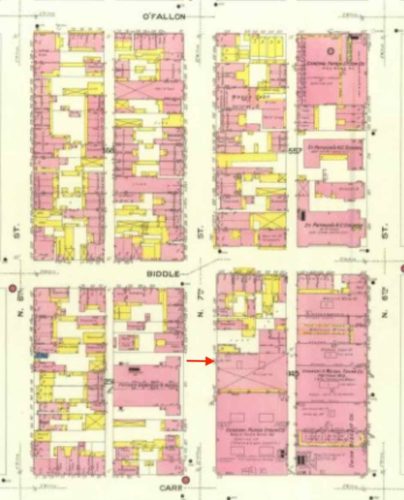

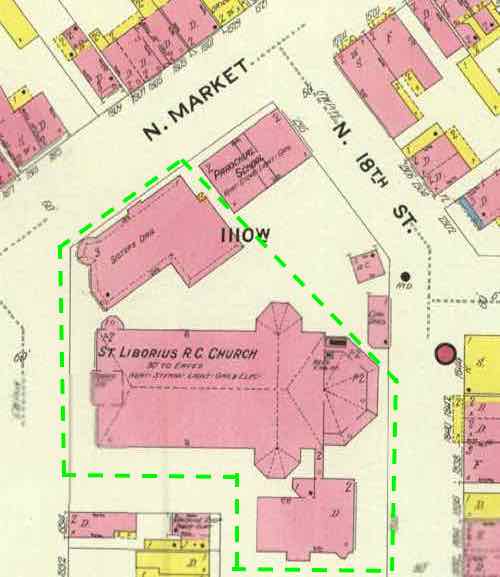

In 1945, an African-American family by the name of Shelley purchased a house in St. Louis, Missouri. At the time of purchase, they were unaware that a restrictive covenant had been in place on the property since 1911. The restrictive covenant prevented “people of the Negro or Mongolian Race” from occupying the property. Louis Kraemer, who lived ten blocks away, sued to prevent the Shelleys from gaining possession of the property. The Supreme Court of Missouri held that the covenant was enforceable against the purchasers because the covenant was a purely private agreement between its original parties. As such, it “ran with the land” and was enforceable against subsequent owners. Moreover, since it ran in favor of an estate rather than merely a person, it could be enforced against a third party. A similar scenario occurred in the companion case McGhee v. Sipes from Detroit, Michigan, where the McGhees purchased property that was subject to a similar restrictive covenant. In that case, the Supreme Court of Michigan also held the covenants enforceable.

— Wikipedia

Interesting the state courts in both Missouri & Michigan found the covenants enforceable. The local civil court ruled against the neighbors…on a technically. Not enough property owners had signed on to enact it.

On October 9, 1945, respondents, as owners of other property subject to the terms of the restrictive covenant, brought suit in the Circuit Court of the city of St. Louis praying that petitioners Shelley be restrained from taking possession of the property and that judgment be entered divesting title out of petitioners Shelley and revesting title in the immediate grantor or in such other person as the court should direct. The trial court denied the requested relief on the ground that the restrictive agreement, upon which respondents based their action, had never become final and complete because it was the intention of the parties to that agreement that it was not to become effective until signed by all property owners in the district, and signatures of all the owners had never been obtained.

Justia

With this 1948 decision many whites decided to leave north city for north county.

— Steve

————————————————————————

St. Louis urban planning, policy, and politics @ UrbanReviewSTL since October 31, 2004. For additional content please consider following on Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon, and/or Twitter.