Four St. Louis High-Rise Public Housing Projects Replaced With Low-Rise Developments

Today’s post is about HOPE VI projects. You may have heard that term before, but if you’re unfamiliar here’s an introduction:

HOPE VI is a program of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. It is intended to revitalize the worst public housing projects in the United States into mixed-income developments. Its philosophy is largely based on New Urbanism and the concept of defensible space.

The program began in 1992, with formal recognition by law in 1998. As of 2005, the program had distributed $5.8 billion through 446 federal block grants to cities for the developments, with the highest individual grant being $67.7 million, awarded to Arverne/Edgemere Houses in New York City.

HOPE VI has included a variety of grant programs including: Revitalization, Demolition, Main Street, and Planning grant programs. As of June 1, 2010 there have been 254 HOPE VI Revitalization grants awarded to 132 housing authorities since 1993 – totaling more than $6.1 billion. (Wikipedia)

The short answer is HOPE VI was the program used to raze & replace distressed high-rise public housing with low-rise mixed-income private housing. With the notable exception of Pruitt-Igoe, all of St. Louis’ high-rise public housing was replaced with low-rise housing — three using the HOPE VI program. Pruitt-Igoe was famously imploded two decades before the start of the HOPE VI program.

From a May 2004 research report after a decade of HOPE VI:

Launched in 1992, the $5 billion HOPE VI program represents a dramatic turnaround in public housing policy and one of the most ambitious urban redevelopment efforts in the nation’s history. It replaces severely distressed public housing projects, occupied exclusively by poor families, with redesigned mixed-income housing and provides housing vouchers to enable some of the original residents to rent apartments in the private market. And it has helped transform the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) approach to housing assistance for the poor. This report provides a comprehensive summary of existing research on the HOPE VI program. Its central purpose is to help inform the ongoing debate about the program’s achievements and impacts, and to highlight the lessons it offers for continuing reforms in public housing policy.

HOPE VI grew out of the work of the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing, which was established by Congress in 1989. Congress charged the Commission with identifying “severely distressed” public housing developments, assessing strategies to improve conditions at these developments, and preparing a national action plan for dealing with the problem. Based on its investigation, the Commission concluded that roughly 86,000 of the 1.3 million public housing units nationwide qualified as severely distressed and that a new and comprehensive approach would be required to address the range of problems existing at these developments.

In response to these findings, Congress enacted the HOPE VI program, which combined grants for physical revitalization with funding for management improvements and supportive services to promote resident self-sufficiency. Initially, housing authorities were allowed to propose plans covering up to 500 units with grant awards of up to $50 million. (Introduction to an Urban Institute report)

I should clarify the HOPE VI program isn’t limited to only remaking high-rise public housing, but that is the type of distressed public housing we had in St. Louis. Other cities, like Chicago, also used it to replace high-rise projects. Cabrini-Green, for example.

Let’s take a look at the four St. Louis high-rise public housing projects that were replaced with low-rise housing built on a more traditional street grid.

Darst-Webbe

This was officially known as the J.M. Darst Apartments and the A.M. Webbe Apartments. The Darst apts., opened in October 1956, occupied 14.75 acres bounded by Lafayette, Hickory, Tucker (12th) & 14th. The four 9-story buildings contained 645 units. The Webbe apts. opened in May 1961 between the Darst apts. and Chouteau. It had a mix of buildings on 12.27 acres: two 9-story, one 12-story, and one 8-story. These four buildings had 580 units. The combined Darst-Webbe then had 1225 apartment units on 27.02 acres.

This was the first high-rise public housing project in St. Louis to be razed and rebuilt under the HOPE VI program. In its place is a mix of apartments and privately-owned single-family homes. On the south is King Louie Square apartments, with 152 1-4 bedroom units. In the middle of the redevelopment site is the single-family homes, called La Saison. Habitat for Humanity is building new homes here on the few vacant lots remaining. The north part of the original site contains more apartments, called Les Chateaux — with 40 1-2 bedroom units.

In 1995 HUD gave the St. Louis Housing Authority a grant of $46.7 million to redevelop Darst-Webbe. Defunct developer Pyramid Construction is responsible for the pretentious names.

Vaughn

This was two projects, both called G.L. Vaughn Apartments. The first, opened in June 1957, was bounded by Cass, O’Fallon, 18th, and 20th. It had four 9-story towers on 16.67 acres — with 647 units. The second opened at the NE corner of 20th & O’Fallon in September 1963. Basically this was just an expansion of the project that opened six years earlier, it had one 8-story building on 2.05 acres, 112 units.

Vaughn was completed, to the best of my knowledge without the use of a HUD HOPE VI grant, but like others it got state low income tax credits.

The partnership event highlighted Phase III of Murphy Park. Its 126 units will bring to 413 the total number of rental dwellings built in the neighborhood that once was the site of the notorious George L. Vaughn public housing high-rises. One third of the completed project will be market rate apartments, with the balance constructed as tax credit units – with just more than half available for public housing-eligible families as part of the replacement of the former public housing complex. Units range from two to six bedrooms and include disability-accessible garden apartments. Each apartment features full size appliances including washer and dryer, refrigerator, stove and dishwasher. McCormack Baron Management Services, the management agent, reports that Phases I and II (completed in 1997 and 2000) have high-90 percent occupancy. Phase III units will be available in March 2003. (HUD)

As the above indicates, this was a McCormack Baron development.

Blumeyer

This was officially the A.A. Blumeyer Apartments. It opened in October 1968, bounded by Compton, Delmar, Grand & Page. It had two 14-story buildings for “elderly”, three 15-story buildings, and forty-two 2-story buildings. There was a total of 1,152 units on 33.90 acres.

This was replaced by the Renaissance Place at Grand apartments and the offices of the St. Louis Housing Authority. To the north, across Dr. Martin Luther King Blvd, Senior Living at Renaissance Place was built on land not part of Blumeyer. Additionally, the North Sarah Apartments were built on…North Sarah… to provide additional units.

The $35 million dollar HUD grant was issued in 2001. Like Vaughn, this was a McCormack Baron project.

Cochran

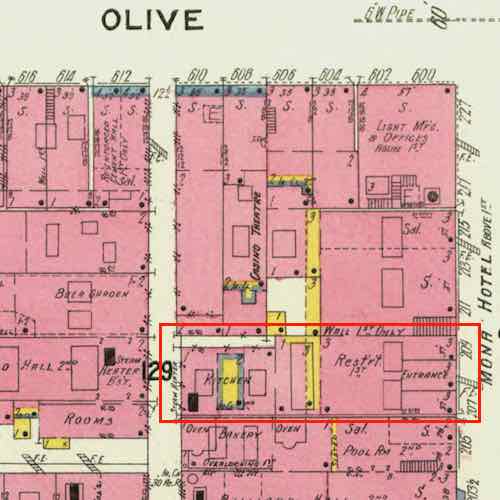

Officially the J.J. Cochran Garden Apartments. Completed in April 1953, it was St. Louis’ first high-rise public housing project — more than two years before Pruitt Homes and three years before Igoe Apartments. The 18.03 acre site contained four 12-story, two 7-story, and six 6-story towers — containing 703 units. It was built to clear out old tenemts businesses on the north edge of the business district didn’t like. Then Cochran became a problem, but tenants pushed for the ability to self manage — and won!

Cochran Gardens was a public housing complex on the near north side of downtown St. Louis, Missouri. Construction was completed in 1953. The complex was occupied until 2006, it was famous for its residents’ innovative form of tenant-led management. In 1976, Cochran Gardens became one of the first U.S. housing projects to have tenant management. Built by the same firm, Leinweber, Yamasaki & Hellmuth, as the infamous Pruitt–Igoe complex, Cochran Gardens was more successful than its ill-fated sister project. In the mid 1970s, Bertha Gilkey and a group of friends successfully led a community driven rehabilitation effort; in 1976 she won a property management contract from the city. Independent management improved Cochran Gardens and created small business jobs in the neighborhood. President George H. W. Bush visited the site in 1991, commending tenant management and Bertha Gilkey. However, in 1998 city authorities took over Cochran Gardens, citing tax mismanagement by the tenant association. The buildings rapidly deteriorated, by 1999 vacancy rate increased from under 10% to one-third. (Wikipedia)

I photographed the area in May 2007 as towers still existed and as new construction was going up, streets going in.

This project was completed by an LLC that includes architect Michael Kennedy of KAI (previously known as Kennedy Associates, Inc). McCormack Baron was management from the very beginning, until February of this year. In a future post I’ll go into more detail on Cochran Gardens & Cambridge Heights.

Summary

These four areas are all significantly better because of each redevelopment. The New Urbanist influence has been a key factor in their success. The buildings in all four orient toward the public street. HOPE VI projects have valid criticism, largely the reduction in the number of public housing units for the very low income. The other is the charge of gentrification, a valid claim in other cities but not in St. Louis. More on that in the future.

— Steve Patterson