Replacing Our Chinatown With A Baseball Stadium Was One Of Many Mistakes

In the 1960s Urban Renewal was in full swing — remaking/destroying cities on a large scale. The majority of people approved — few protested. The powers that be had dismissed Jane Jacobs’ 1961 critique: The Death & Life of Great American Cities.

Forty city blocks of our original city had been vacant for a quarter century when Time magazine wrote the following on July 17, 1964:

In all, some $2 billion worth of major construction is under way or planned in the metropolitan area. A 454-acre midtown tract of slums called Mill Creek Valley, filled with slum housing that cried out for rebuilding in 1954, is now one of the largest urban-renewal areas in the U.S. A substantial section of it will be set aside for an expressway to link downtown with the major expressways leading out of the city. The long neglected riverfront has been cleared for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Park; scheduled for completion there next year is a soaring stainless-steel arch 630 ft. high, designed by the late Eero Saarinen as a monument to St. Louis as Gateway to the West. A seven-block pedestrian mall shaded by trees and flanked by lawns is abuilding. Ground has been broken for a 1,100-car parking garage, first step in construction of a downtown sports stadium, designed by Edward Stone, that will seat 50,000, cost $89 million.

The program has its critics. The Mill Creek slums were bulldozed in 1960, but redevelopment has been so slow that the area is locally dubbed “Hiroshima Flats.” The New York Times’s Ada Louise Huxtable charged that the rebuilders had razed “the heart and history” of the city by clearing the riverfront. Defenders point out that the storied waterfront had long deteriorated into a grimy morass of dilapidated warehouses, buildings and residences. Developers have been scrupulous in preserving the architectural monuments of the area—the old courthouse and the cathedral—and have stored the best examples of cast-iron storefronts to be put on display in the new Museum of Westward Expansion. (Time)

“But these areas were bad, they had to be razed,” you might say. That was the propaganda constantly sold the public. Another such bad area that needed to be razed? The Soulard neighborhood (see 1947 reconstruction plan). Basically if they wanted to remove something a campaign was waged to build public support. Often, there were racial motivations.

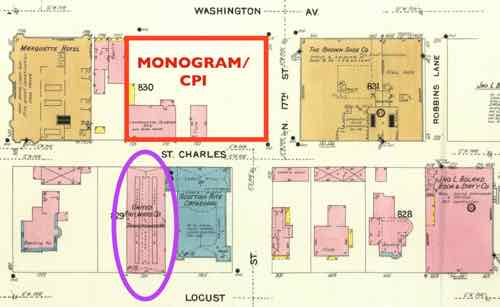

The neighborhood razed for Pruitt-Igoe was Irish. Mill Creek Valley was African-American. And what became Busch Memorial Stadium (1966-2006) had been our Chinatown since the 19th century:

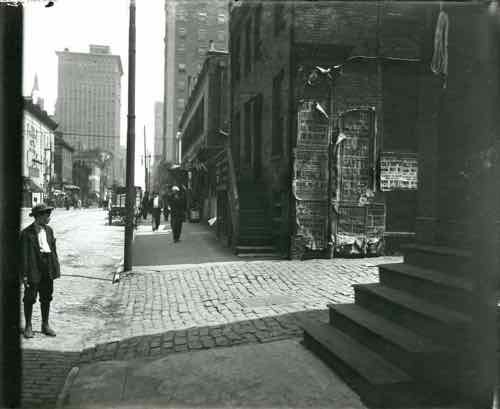

The first recorded Chinese immigrant was a tea merchant named Alla Lee, who is reported to have arrived in 1857 from San Francisco. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese community in St. Louis had grown to about three hundred. This community was physically centered in “Hop Alley,” a seemingly mysterious place that inspired tall tales to the contemporaries and is little known to the present St. Louisans. Along Seventh, Eighth, Market, and Walnut Streets, Chinese hand laundries, merchandise stores, grocery stores, restaurants, and tea shops were lined up to serve Chinese residents and the ethnically diverse larger community of St. Louis, the fourth largest city in the United States at the time.

Downtown businesses wanted the gleaming new modern downtown and Chinese-Americans doing laundry didn’t fit that image. They must go! But how? At this same time those who pushed wholesale razing of large areas knew cultural institutions were a good excuse to raze existing areas — forcing the inhabitants to be relocated. Working with Cardinals owner Anheuser-Busch, the process began to push Chinatown out of downtown. This would also put the team closer to the brewery.

In February 1968 New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote the following about downtown St. Louis:

Except for the arch and the old courthouse, which form some genuinely provocative urban views, downtown St. Louis is a monument to chamber of commerce planning and design. It is a businessman’s dream of redevelopment come true.

There are all the faceless, characterless, scaleless symbols of economic regeneration — luxury apartments, hotels, a 50,000 seat stadium and multiple parking garages for 7,400 cars. Sleek, new, prosperous, stolid and dull, well served by superhighways, the buildings are a collection of familiar profit formulas, uninspired in concept, unvarying in scale, unrelated by any standards, principals or subtleties of planning or urban design. They just stand there. They come round, rectangular, singly and in pairs. Pick your standard commercial cliche.

The new St. Louis is a success economically and a failure urbanistically. It has the impersonal gloss of a promotional brochure. A prime example of the modern landscape of urban alienation, it has gained a lot of real estate and lost a historic city. (“Hop Alley”: Myth and Reality of the St. Louis Chinatown, 1860s-1930s)

Much of downtown remains faceless, characterless, and scaleless. The area where baseball had been played since the 19th century suffered from the loss of jobs & activity. One institution resisted the trend to locate in a modern downtown building, the symphony instead restored an old movie palace. Ada Louise Huxtable again:

The success of Powell Symphony Hall in St. Louis is probably going to lead a lot of people to a lot of wrong conclusions. In a kind of architectural Gresham’s law, the right thing wrongly interpreted usually has more bad than good results.

The first wrong conclusion is that Powell Hall represents the triumph of traditional over modern architecture. False. The correct conclusion here is that a good old building is better than a bad new one. Powell Hall represents the triumph simply of suitable preservation. And, one might add, of rare good sense.

Very rare in St. Louis. We can’t change the past, so why keep harping on it? Because we’ve not learned from our past mistakes! We keep repeating, at least attempt, to repeat them.

Readers were split in the non-scientific Sunday Poll:

Q; Agree or disagree: Building the new baseball stadium downtown in 1966, instead of in a neighborhood, was a bad decision

- Strongly agree 5 [11.63%]

- Agree 6 [13.95%]

- Somewhat agree 9 [20.93%]

- Neither agree or disagree 3 [6.98%]

- Somewhat disagree 4 [9.3%]

- Disagree 9 [20.93%]

- Strongly disagree 6 [13.95%]

- Unsure/No Answer 1 [2.33%]

Those who agreed totaled 46.51%, while those who disagreed totaled 44.18%.

We can’t undo the past mistakes, but the disastrous Urban Renewal mindset is still alive in 2016 St. Louis.

— Steve Patterson