A Tour of City Foundry St. Louis, the Food Hall, and Fresh Thyme Market

Today’s post is a look at City Foundry St. Louis, a new retail & office development in an old foundry along Forest Park Ave., between Spring and Vandeveter.

Almost 100 years ago, the Century Electric company purchased the Midtown St. Louis property now known as City Foundry STL. At the time, Midtown was a manufacturing hub for the city, thanks to its proximity to the Wabash Railroad line, which cuts across the City Foundry STL Property.

Century Electric was one of the top 3 manufacturers in the city, manufacturing motors and generators that were sold internationally. In fact, Century’s motors helped spark the development of small household appliances.

While the foundry changed owners over the years, and the products produced there changed, one thing did not: nearly 24-hour-a-day work continued on the site until 2007.

Today, this 15-acre site is being reimagined as City Foundry STL, with first-to-the-area makers and merchants moving to the complex. We can’t wait to for you to be a part of the next chapter of this storied creative complex. (City Foundry St. Louis)

First, a definition:

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals processed are aluminum and cast iron. However, other metals, such as bronze, brass, steel, magnesium, and zinc, are also used to produce castings in foundries. In this process, parts of desired shapes and sizes can be formed. (Wikipedia) [An aside: a segment from a 1997 Simpsons episode comes to mind]

I’ve lived in St. Louis for over 31 years now, but don’t recall the name Century Electric. My memory of the foundry was the smell making automotive brake parts for Federal-Mogul. My post from last month: A Look at City Foundry St. Louis…in August 2013.

The 1909 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show a few scattered wood frame buildings in this area, not a foundry. City records list four buildings on the site:

- Manufacturing 1932: 146,015 square feet

- Warehouse 1937: 66,197sf

- Warehouse 1953: 38,640sf

- Manufacturing 1982: 5,760

Let’s take a look, getting into some history along the way.

I wanted to know more about Century Electric so I began scouring the Post-Dispatch archives online via the St. Louis Public Library. Here’s a bit of what I found in a Post-Dispatch article from December 25, 1949, P61:

- Century Electric organized 1900, incorporated 1901

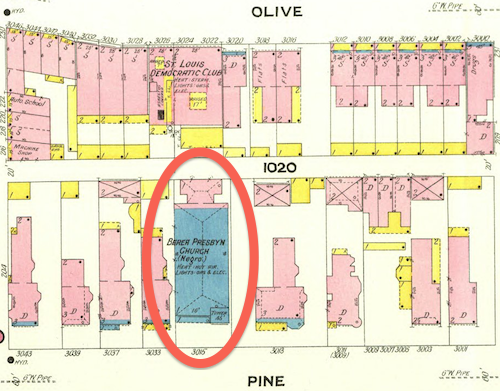

- first workshop an old church at 1011 Locust

- first working motor tested on thanksgiving day 1903 — sold to Rosenthal-Sloan Millinary Co.

- products shipped to 90 foreign countries

- first to offer repulsion type motor in small sizes

- a century motor was in the first successful home refrigerator

- manufactures everything except the wire

- foundry address is/was 3711 Market Street — before I-64/Hwy 40 went though.

Let’s resume the tour.

Let’s go out to Forest Park Ave and approach from the west.

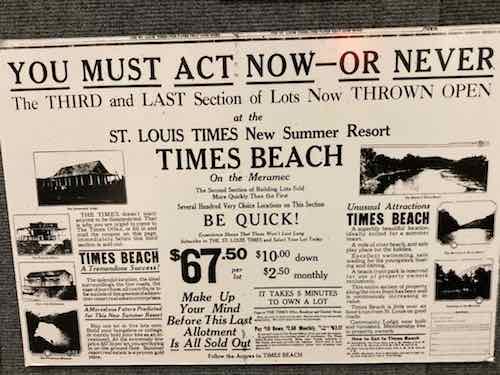

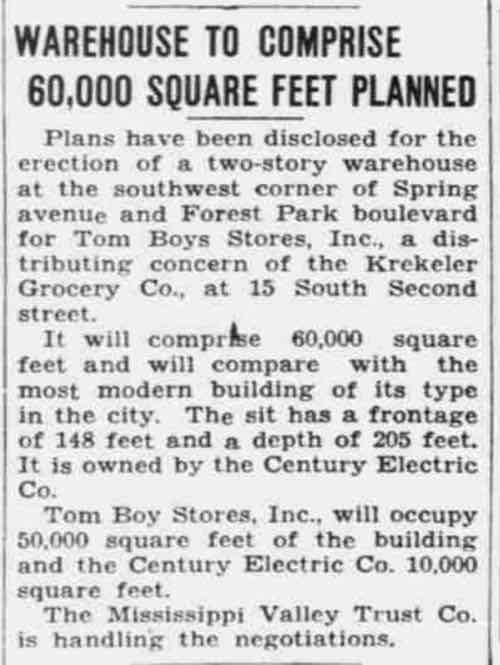

One last exterior area to show you, the building on the SW corner of Forest Park & Spring avenues. It began as the new offices of a local grocery chain, so using it for a new grocery store is very fitting. From the Post-Dispatch July 18, 1937:

Let’s go inside Fresh Thyme, later we’ll go into the Food Hall.

Fresh Thyme Market has other locations in the region, on both sides of the river. The grocery chain in based in suburban Chicago (Downers Grove, IL). The large chain Meijer is an investor, their nearest location is Springfield IL. So you’ll see some Meijer products on shelves.

On opening day I planned to get a package of Meijer frozen tuna steaks that I priced on the Fresh Thyme’s website (Kirkwood location). At this new location the very same item was 50% more than in Kirkwood. WTF!?! I ask the manager why the price is so much more. The answer was unexpected. The Fresh Thyme Market at City Foundry STL isn’t part of Fresh Thyme’s system, including pricing. Fresh Thyme investor Meijer is a partner on this location, so the pricing is based on that. The manager told me they’d match the significantly better price at checkout. To this day if you do a search on the actual Fresh Thyme website for the nearest location it won’t find the City Foundry location. It’s not on the Meijer website either. Very weird.

Other than the frozen tuna steaks the prices I’ve checked have all been reasonable, their milk price is the best I’ve seen anywhere in the region. We’ve been back numerous times, a welcome new addition. Now if they’ll just stop filling the ADSA-compliant accessible route with extra shopping carts.

Moving on, let’s visit the Food Hall. First, a food hall is not the same as a food court:

Here are 4 things about food halls and what makes people love them:

-

Food halls are usually a collection of small, locally-developed restaurant concepts or outright new creations that come from the minds of local chefs or start-up entrepreneurs and restauranteurs. They offer an assortment of unique food and beverage items that are usually cooked from scratch (prepared from raw ingredients vs. shipped in partially or wholly made) or nearby in a commissary (but still from scratch). On the other hand, food courts are usually filled with national chain restaurants that offer little scratch cooking and little-to-no brand cache.

-

Food courts will typically feature a cast of usual players like one or two Asian concepts (with one or both of them serving a version of Bourbon chicken), an ice cream place, a pizza place, a burger chain or two, a Latin concept, a hot dog concept, a cheesesteak concept, and maybe a cookie place. The dining options in a food hall are more in line with a collection of food trucksat a food truck park than the food found in a food court, with ethnic favorites like Vietnamese bao buns, Cuban street sandwiches, wine and cheese, Italian sandwich or pasta shop, local ice cream or gelato, chocolatiers, or Napolitano style pizza (vs. Sbarro’s par-cook-n-reheat slices), southern fried chicken sandwiches, and just about anything you can imagine.

-

Food halls are aesthetically pleasing, often in turn-of-the-century warehouses, train stations, or old mills with high ceilings where the building’s history is partially or mostly preserved. Ponce City Market was originally a Sears & Roebuck distribution warehouse. Chelsea Market in New York was a Nabisco factory where the Oreo was invented. Quincy Market in Boston is one of the oldest food halls in America (it was a food hall before folks started calling them food halls) and sits next to historic Faneuil Hall…it was designed from the beginning (1824-1826) to be a marketplace. In a food hall, the charm of historic significance combines with the unique food offerings and the novelty of reclaimed industrial space to form a city’s social nucleus, while food courts are really little more than uninspired feeding pit stops for mall shoppers.

-

Food halls are destinations. Retail stores are few and are injected to add interest and shopping-as-entertainment to the food experience, but they must convey a consistent lifestyle “voice” to their visitors. Anthropologie, Lululemon, or Madewell are common national retail supplements. Food courts are designed to keep shoppers shopping so they don’t leave the mall when they get hungry… the food supports the shopping, not the other way around like in a food hall.

Ready?

Concluding thoughts on City Foundry St. Louis

I was very happy & curious when I first heard the developers planned to keep the old industrial buildings rather than scrape the site clean. Overall I’m pleasantly surprised by how they’ve turned an old dirty industrial site into a retail & office destination. If you haven’t been I recommend visiting.

Transit users can take MetroLink to either Grand or Cortex, the nearest bus lines are the 42 & 70.

— Steve Patterson