St. Louis’ Original “Little Italy” Neighborhood: North Downtown/Columbus Square

When you think of an Italian neighborhood in St. Louis, The Hill naturally comes to mind.

The Hill’s roots are interspersed with the history of St. Louis, generating two of the region’s proudest exports – world-class athletes and Italian cuisine. Baseball’s Yogi Berra and Joe Garagiola grew up here, and today it maintains a traditional collection of authentic Italian bakeries, grocery stores, restaurants and mom-and-pop trattorias.

Everything is colorful here – even the fire hydrants are painted red, white and green. Twenty-first century additions include coffee houses, studios, retail and small businesses that create additional energy in the cozy enclave. Its epicenter is one intersection that sums it up perfectly, with St. Ambrose Catholic Church on one corner, an Italian bakery/restaurant on another, an import shop across the street, and a neighborhood tavern/bocce garden on the fourth corner. (Explore St. Louis)

In the late 19th & early 20th century immigrants from Sicily first settled in the ethnically diverse neighborhood on the North edge of the Central Business District and further North — the southern part of today’s Columbus Square neighborhood.

The Italians came to St. Louis in the late 1880s. They lived in what is now downtown St. Louis among the Germans, Greeks, and Irish and attended St. Patrick’s Catholic Church or Our Lady Help of Christians in an area referred to as Little Italy, along Cole Street.

In the early 1900s, the Italians started another community southwest of Little Italy called The Hill. By the mid-1900s, most Italians had left Little Italy and moved to The Hill. (St. Louis Genealogical Society)

By the time they arrived the shopfronts, flats, and tenements were already old. In addition to the races mentioned above, Jewish families also called the neighborhood home.

Before going further it’s important to note that today’s boundary lines didn’t exist. Highways didn’t cut through neighborhoods, wide streets like Cole were the same width as Carr. Cole wasn’t even called Cole.

Here’s a look at East-West street names and what they were called in 1909, starting at Washington Ave and going North to Cass:

- Washington Ave was Washington Ave

- Lucas Ave was Lucas Ave

- Convention Plaza was Delmar, called Morgan in 1909. (Could’ve been the Morgan divide?)

- Dr. Martin Luther King was Franklin

- Cole was Wash

- Carr was Carr

- Biddle was Biddle

- O’Fallon was O’Fallon.

- Cass was Cass

Again, Cole today is a very wide street that separates Downtown from Columbus Square. Like Franklin to the South, and Carr to the North, it was a normal neighborhood street — not a dividing line.

Major change came as the city decided to widen comfortable neighborhood streets like Franklin. Everything in the photo above has been part of the convention center since the mid-1970s. One neighborhood spaghetti joint became St. Louis’ top restaurant — Tony’s:

Before Tony’s, the Bommarito family had St. Louis’ first Italian bakery. It was at 7th and Carr Streets, plus they operated a spaghetti factory at 10th and Carr. Tony’s was created by Anthony Bommarito in 1946, and, in its earliest life was a small café, soon to be called Tony’s Spaghetti House and by the early 1950s Tony’s Steak House. It was located just north of the heart of downtown at 826 N. Broadway between Delmar Boulevard (formerly Morgan St.) and Franklin Avenue in the old Produce Row district at the edge of the soon to disappear Little Italy neighborhood. Family names of those who lived nearby included: Polizzi, Impostato, Olivastro, Lapinta, Viviano, Difirore, Impielizzeri, Tocco, Arrigo, Marino and Capone. (Tony’s)

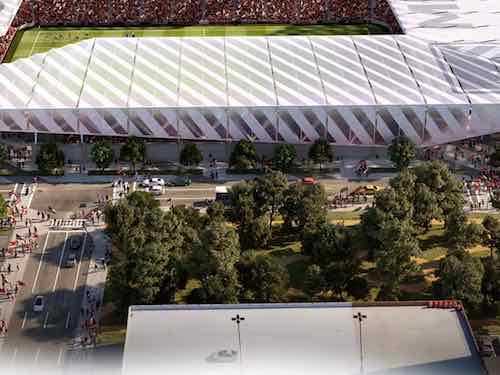

In the early 1990s Tony’s was forced to relocate because of the construction of the football stadium being built to get an NFL expansion team. Ton’y was on the East side of Broadway, part of today’s Baer Plaza. As indicated above, Broadway was also part of Produce Row, before moving to 2nd & North Market in the 1950s. [Produce Row history]

At least one Italian immigrant from the neighborhood likely worked at Produce Row: Frank Cammarata.

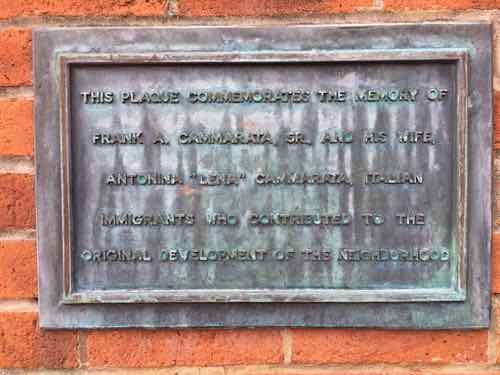

This little plaque is why I began looking into Italian immigrants into the neighborhood. Here’s what I’ve learned through a lot of digging:

Frank Cammarata’s middle name was William. He was born in Italy and came to the states on August 28 1913, via Canada. A Joseph Cammarata was already in St. Louis, presumably his brother, with various addresses over the years: 614 Biddle, 616 Biddle, 618 Biddle, 1003 N 6th, and 1121 N 11th. In 1915 Frank Cammarata was living at 805A Carr.

Directories & census listed Frank as a fruit pedlar, though he was no longer working by the 1940 census. Lena Cammarata died in late August 1939, they were living at in the Shaw Neighborhood at 4152 Castleman. Frank Cammarata died in 1950 at age 72, still living in Shaw on DeTonty.

The Cammarata’s were already living on Castleman in 1929. I contacted the apartment complex owner, the Mills Group, online to see if they knew anything. They never responded. I stopped by the apartment leasing office to ask. Due to many steps I couldn’t enter, so I called and two women came out to chat. They didn’t even know a plaque existed. They suggested I ask the city, though the plaque is on their private property.

One of the Cammarata’s sons was Frank A. Cammarata, Jr. (1912-1986). My assumption is the 1981 plaque got put up because of him, but the maker goofed and put the son’s middle initial “A” instead of the father’s “W”. I’ve been unable to find anything to substantiate how they contributed to the “original development of the neighborhood” — especially since the neighborhood was already old when they were born in Italy.

As one of the oldest neighborhoods, the building stock was old. Many of the 1909 Sanborn Fire Insurance map pages indicate the neighborhood buildings are old, many are tenements. In 1937 a private housing project, Neighborhood Gardens, was built on a single block. It had goal of providing affordable housing to low-income neighborhood residents. It failed, as the rents needed to be higher than anticipated to cover obligations.

When the federal government got into the low-income housing business the neighborhood was the site of one of the city’s first high-rise public housing projects: Cochran Gardens. It opened in 1953, a year before Pruitt-Igoe located, due west. This brings me to the story of two of the last old Italian-American businesses in the neighborhood.

From the Post-Dispatch November 9, 1936 page 33 of 36 [a daily special section)

For the last 31 years the Rosciglione family has been, by popular appointment, official confectioners to the Italian-American population of St. Louis. For 31 years the Roscigliones, brothers and father, have been shaping almond paste fruits and flowers, molding hard sugar scenic pieces and baking rich cakes for a critical clientele. No wedding, birthday, feast day, church or State holiday has been properly observed in Italian-American homes without some sweet, traditionally symbolic of the day, from the Rosciglione kitchens at 1011 1/2 North Seventh Street.

This would’ve been on the west side of 7th Street between Wash (now Cole) and Carr. Later in the same article:

When Frank Rosciglione came to this country in 1906 from Palermo, one brother, Tony, already in St. Louis and had a small confectionary shop on Eighth street. Business was good, so he sent for his brother, this time Frank. Shortly afterwards, the two moved their pastry tubes, baking pans and molds over to the Seventh street location. The next year business had increased again so they sent for another brother, Dominick. When they thought they were pretty well on their feet, in 1911, they sent for their mother and father who still kept the confectioners shop in the Old Country. Now all are gone except Dominick who carries on the family profession with one helper and his oldest son.

More than 15 years after Cochran Gardens opened, the neighborhood had changed. The shiny new housing project was losing its luster. Rent strikes were happening at Cochran, Pruitt-Igoe, and other housing projects.

The Post-Dispatch on July 20, 1969 page 119 of 338 had a story about the last two Italian-American businesses leaving the neighborhood, not for The Hill, but St. Louis County.

“We cannot endanger our customers,” said tall, sandy-haired Peter Rosciglione, 47 years old. He was explaining why he was closing his 70-year-old bakery at 1011 North Seventh Street. He and his wife, Josephine, and their son, Peter, have packed up the bride-and-groom figures for the tops of wedding cakes, the ornate, old-fashioned candy jars, the molds for three-foot sugar dolls. All these things will be carefully placed in their new store in St. Louis County, at 9839 West Florissant Avenue, Dellwood.

Rosciglione related that in the last month, six customers were approached by innocent-looking small boys who asked for the time, snatched the exposed watches and ran. His shop and the Seventh Street Market, a meat market at 933 North Seventh Street, have been robbed “over and over again” after hours, though the shopkeepers have not been held up.

“I work with this on the counter,” he said, holding up a pistol. “We have to walk with our women customers to their cars to keep them from having their purses snatched. Recently I heard that because we were spoiling the purse-snatching business for the juvenile gang, that they were out to get me.”

“This is just one mass jungle,” Rosciglione said. “The good families who live nearby in the Cochran housing project and in the neighborhood are as terrified of the gangs as our customers are. I can’t allow them to jeopardize themselves for our merchandise any more.

Rosciglione Bakery still exists today…in St. Charles, MO.

Vincenzo Rosciglione came to the United States in 1898 from Palermo, Sicily. He opened the first Italian Bakery in downtown St. Louis at 1011 North 7th Street. The bakery was well received by the large Italian community in the downtown area known as “Little Italy“.Vincenzo’s son, Francesco, still in Sicily studying under a famous pastry and sugar artist, was sent for at the age of 16. He and his wife, Cosimina, ran the well established bakery until his death in 1949. After working under the tutelage of his father for many years, Peter and his wife, Rose, took over the bakery.The bakery left downtown St. Louis in 1969 and opened in Dellwood, Mo. where it remained until 1997. Rosciglione Bakery then moved to it’s present location in St. Charles, Mo. where it continues to be family owned and operated by 4th generation, Francesco Peter Rosciglione. (Rosciglione Bakery)