State & Local Leadership Have Failed To Learn From Mistakes Of The Last 75+ Years

I’d like to think that after decades of leadership pushing projects that clear many acres of buildings, streets, sidewalks, utilities, etc., that someone in city hall or Jefferson City would realize that such projects are costly follies that never live up to the promises. Some examples:

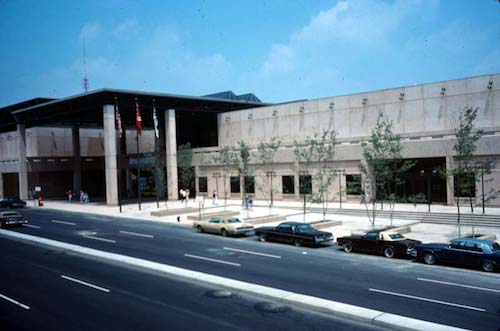

There have been countless other projects; including highways that separated neighborhoods, warehouses that destroyed the street grid, etc. In 1988 the city began discussing buying the Sheraton Hotel, located immediately east of the Cervantes Convention Center to expand and build a football stadium, the 600+ room hotel wasn’t even a decade old when talk began of razing it to expand the convention center and build a domed stadium.

As politicians smiled and sweated in Monday morning’s 89-degree heat, ground was broken for the $260 million stadium expansion of Cervantes Convention Center. The building, scheduled for completion by October 1995, will seat 70,000 for professional football. With 177,000 square feet of exhibit space on one level, it will accommodate events as large as national political conventions. During the hour-long ceremonial groundbreaking at Seventh Street and Convention Plaza, demolition crews began swinging a giant ”headache ball” at the old Sheraton Hotel, one block north. Each swipe at the 13-year-old hotel, which sits near the 50-yard-line of the stadium expansion, brought cheers. But the sturdily built hotel was slow to succumb to the headache ball. (Post-Dispatch Tuesday, July 14, 1992)

I was just 25 when demolition began on a tall hotel that wasn’t even 15 years old, but it was worth a couple of shots on my roll of film.

Razing the hotel built to serve conventions meant we had to build another convention hotel, the Renaissance Grand has lost money since opening.

“Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”

— Albert Einstein

Tomorrow I’ll post about the particulars of the latest St. Louis folly: last friday’s proposal for a new NFL/MLS stadium to convince billionaire Stan Kroenke from moving the Rams back to Los Angeles.

— Steve Patterson