The St. Louis Region Should’ve Planned For Commuter Rail A Century Ago

In thinking about transit in other regions compared to ours, it is clear to me that natural geography and historic development patterns play a role in transportation planning in the 21st century. Decisions made a century ago, good & bad, still affect us today.

One hundred years ago St. Louis hired a 26 year-old civil engineer, Harland Bartholomew, to be its first planner. During the previous 151 years it developed organically, without planning, He quickly proposed widening many public rights-of-way (PROW) to make room for more cars.

St. Louis city invested heavily in widening streets like Natural Bridge, Jefferson, Gravois.

More than three decades after arriving in St. Louis, Bartholomew got a Comprehensive Plan officially adopted (1947). His plan was all about remaking St. Louis because it would have a million residents by 1960 — or so he thought!

Here’s the intro to the Mass Transportation section:

St. Louis’ early mass transportation facilities consisted of street car lines operated by a considerable number of independent companies having separate franchises. Gradually these were consolidated into a single operating company shortly after the turn of the century. In 1923 an independent system of bus lines was established but later consolidated with the street car company. Despite receivership, re-organization and several changes of ownership the mass transportation facilities have been kept fairly well abreast of the city’s needs. Numerous street openings and widenings provided by the first City Plan have made possible numerous more direct routings and reduced travel time.

Approximately 88 per cent of the total area of the city and 99 per cent of the total population is now served directly by streetcar lines or bus lines, i.e., being not more than one quarter mile walking distance therefrom. Streetcar lines or bus lines operate directly from the central business district to all parts of the city’s area. There are also numerous cross-town streetcar lines or bus lines, operating both in an east-west and north-south direction.

No mention of a regional need for commuter rail. Some might point out this was the city’s plan, not the region’s. That would be a valid point if it weren’t for the regional nature of the next section: Air Transportation:

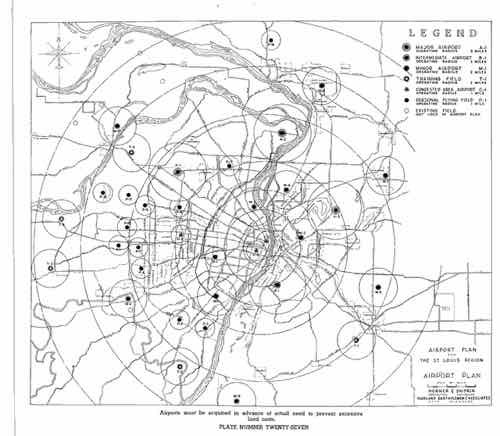

It is reasonable to assume that the developments in air transportation during the next few decades will parallel that of automobile transportation, which really started about three decades ago. St. Louis must be prepared to accept and make the most of conditions that will arise. Provision of the several types of airfields required must be on a metropolitan basis. The recently prepared Metropolitan Airport Plan proposes thirty-five airfields. See Plate Number 27. These are classified as follows:

- Major Airports – for major transport 3

- Secondary Airports – for feeder transport 1

- Minor Fields – for non-scheduled traffic, commercial uses and for training 15

- Local Personal Fields – for private planes 13

- Congested Area Airports – for service to congested business centers 3

[Total] 35Of these, two major, eight minor, twelve personal and three congested area airports would be in Missouri. Lack of available land in the City of St. Louis limited the number within the corporate limits to two minor, one personal and two congested area airports. The selection of sites for the latter involves great cost and should await further technological developments in design and operation of various types of aircraft, including the small high powered airplane, the autogyro and the helicopter.

The three airports within the city are:

- A Minor Field at the southern city limits east of Morganford Road.

- A Minor Field in the northern section of the city between Broadway and the Mississippi River. (Since the publishing of the above report this field has been placed in operation by the city.)

- A Local Personal Field in the western section of the city on Hampton Boulevard north of Columbia Avenue.

The latter is of special significance because of the great concentration of potential private plane owners in fairly close proximity. The northern minor field is adjacent to a large industrial area. The southern minor field would also serve a large industrial area as well as a considerable number of potential private plane owners.

So the region should have 35 airports but no commuter rail service? It should have numerous new highways but no commuter rail? Here’s the visual of the region with 35 airports:

Thirty-five airports but no plan for mass transit beyond bus service?

Bartholomew left St. Louis in 1953 to chair the National Capital Planning Commission, where he created the 1956 plan for 450 miles of highway in the capital region.

During the 1960s, plans were laid for a massive freeway system in Washington. Harland Bartholomew, who chaired the National Capital Planning Commission, thought that a rail transit system would never be self-sufficient because of low density land uses and general transit ridership decline. But the plan met fierce opposition, and was altered to include a Capital Beltway system plus rail line radials. The Beltway received full funding; funding for the ambitious Inner Loop Freeway system was partially reallocated toward construction of the Metro system. (Wikipedia)

A book written by a partner of Bartholomew revises history to suggest he pushed for Washington’s Metro — see Chapter 10.

https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/archive/harland-bartholomew/HBaACh10.pdf

Washington has fewer miles of freeways within its borders than any other major city on the East Coast.” Thirty-eight of the planned 450 miles would have routed through D.C. proper; today, there are just 10. Instead, after a wrenching and protracted political battle, they write, “the Washington area got Metro—all $5 billion and 103 miles of it.” (Slate)

In 1945, as a paid consultant, Bartholomew said “the density of population of the Washington area would never be sufficient to warrant a regional rail system.” (Lovelace P141, chapter 10 p3). Most likely he felt that way about the St. Louis region. Though the city was quite dense during his decades here, the surrounding suburbs were low-density, still are.

But what if he had guided the region to develop boulevards to the North, West, & South of downtown with streetcars in the median? Today that right-of-way could be used for light rail. Cleveland, for example, is fortunate that Shaker Blvd & Van Aken Blvd were planned as such, providing room for their Green Line & Blue Line, respectively.

Bartholomew was highly influential — the one person in the region that might have been able to lay the ground work for better mass transit in the 21st century. It wasn’t feasible like lots of highways & airports.

My point is when we think about future transportation infrastructure, and we look at other regions, we must keep in mind their planning & development decisions a century ago. Many still think we should’ve put light rail down the center of I-64 during the big rebuild — failing to realize there wasn’t a way to get a line into the center and it wouldn’t work well if we could since the housing along the route wasn’t developed around transit.

We were able to leverage rail tunnels under downtown and a rail corridor to get light rail to the airport. Other former rail corridors exist for new light rail lines, such as North along I-170 out of Clayton into North County. We do have excessively wide boulevards in the city & county, but cutting up the street pattern after the fact by putting light rail down the center and significantly reducing crossing points is similar to building a highway — it separates.

Moving forward with plans for new regional transportation infrastructure we must recognize we simply don’t have the advantages many other regions enjoy. We can’t go back and undo decisions Bartholomew & others made a century ago.

— Steve Patterson