Soldiers’ Memorial Kicked Off Demolishing Our City’s Center

Last month, on the 28th, Soldiers’ Memorial closed for a 2-year renovation. Soldier’s Memorial is St. Louis’ tribute to those who died in World War 1.

The Soldiers Memorial Military Museum closed Sunday for a $30 million renovation, with promises of reopening in two years as a functional and inspirational “transformation.”

It is the first lengthy closure of the 80-year-old downtown landmark.

The Missouri Historical Society and local public officials held a flag lowering ceremony Sunday afternoon to mark the occasion. (Post-Dispatch)

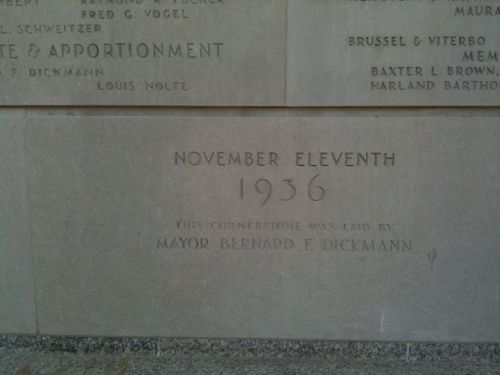

The 80th anniversary of the cornerstone isn’t until this fall. It opened to the public on Memorial Day. May 30, 1938.

The project began in the 1920s:

The City of St. Louis created a Memorial Plaza Commission in 1925 to oversee the creation of the Memorial Plaza and Soldiers Memorial. Designed as a memorial to the St. Louis citizens who gave their lives in World War I, the Memorial became Project No. 5098 of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works. The St. Louis architectural firm Mauran, Russell & Crowell designed the classical Memorial with an art deco flair and St. Louis-born sculptor Walker Hancock created four monumental sculpture groupings entitled Loyalty, Vision, Courage and Sacrifice to flank the entrances. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the site on October 14, 1936 and two years later Soldiers Memorial Military Museum opened to the public on Memorial Day, May 30, 1938. (Missouri History Museum — Soldiers’ Memorial)

In 1925 St. Louis hadn’t begun razing the blocks between Market & Chestnut, 11th and 20th. The Civil Courts building began in 1928, Aloe Plaza in 1931. Demolition of the original city on the bank of the Mississippi River didn’t commence until 1939. A war memorial was what St. Louis’ planner, Harland Bartholomew, needed to justify taking & razing private property just West of the Central Business District.

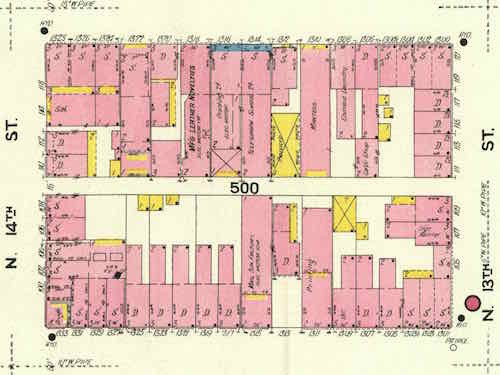

The block with Soldiers’ Memorial is bounded by 13th, Chestnut, 14th, and Pine, it looked very different in 1909:

Granted, none of these buildings were notable, no special businesses were displaced. It was rather ordinary, in fact. But this one block contained nearly 50 structures, with entrances on all four streets — it helped generate urban activity. To many born in the late 19th century such blocks were viewed as chaos.

Taking out one active block does little to change the vibrancy of a city, but when it’s repeated over and over it has a hugely negative impact. The 1940 census showed a drop in population — at least partially as a result of massive demolition in the 1930s. At the time they thought the population would continue growing — exceed a million by 1960. They couldn’t see their actions contributing to massive population declines in the coming decades.

The Soldiers’ Memorial building is very formal — especially compared to the nearly 50 buildings that previously occupied the block. Let’s take a look.

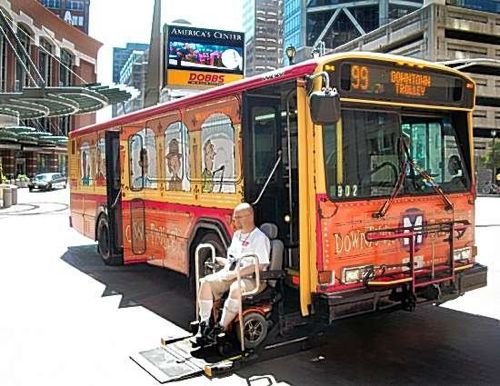

Yes, St. Louis built a war memorial that many disabled veterans couldn’t visit! Not uncommon for the era — the disabled were routinely institutionalized then. Apparently the building had an outdoor mechanical lift that failed in 2004, leaving a disabled vet stranded. It was that event that prompted the effort to build ramps outside.

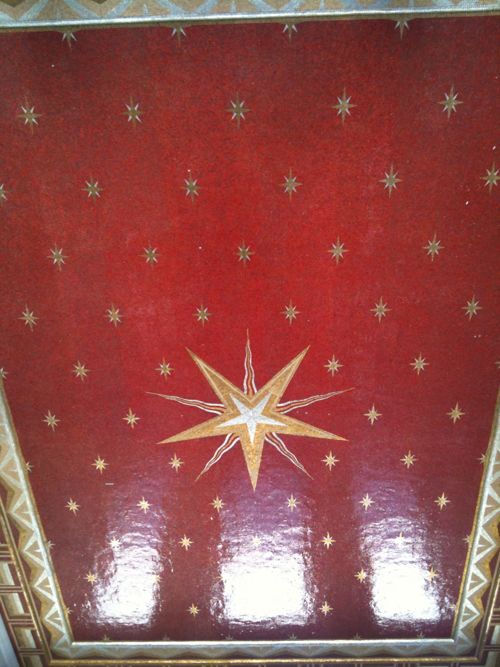

I love many of the interior details (floors, ceilings, rails, lights, elevator. etc) but they missed the big picture. The outdoor WWII memorial, the Court of Honor, in the block directly south also wasn’t accessible when it opened a decade later on Memorial Day 1948.

Since St. Louis has given up on the Gateway Mall Advisory Board I’m nervous above what’ll happen here.

— Steve Patterson