As we debate a new NFL stadium it’s important to understand the history going back nearly three decades. For that I asked Heywood Sanders, Professor of Public Administration at the University of Texas at San Antonio, if I could publish an excerpt from his book Convention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American Cities, which I posted about in December. He agreed, sending me the requested text.

The following is from Chapter 8 on St. Louis’ convention center:

The successful passage of the expansion taxes assured more space for the Cervantes Center. But the issue of an attached domed stadium was still unresolved at the end of 1987, as was the future of the Cardinals football team. In late October Bill Bidwell had announced plans to move from St. Louis, and had begun to flirt with city officials in Phoenix, Baltimore, and Columbus. In a last-ditch effort to keep the team in St. Louis, Governor John Ashcroft and Charles Knight, representing Civic Progress, made a final offer to Bidwell, including a new 70,000-seat domed stadium adjacent to the convention center (to be jointly financed by the city, county, and state) and a guarantee of $5 million a year in additional income to the team from Civic Progress companies. Despite the promises, Bidwell announced in mid-January 1988 that he was moving the team to Phoenix. [161]

The loss of the team was termed by an editorial in the Post-Dispatch as “a blow to the area’s economy as well as its pride.” If so, it was a blow the Civic Progress leaders were entirely unwilling to accept. The business leaders continued to press for state legislation creating a Regional Convention and Sports Complex Authority to finance construction of a domed stadium adjacent to the convention center, with the hope that passage could persuade the National Football League to intervene and halt the proposed move to Phoenix. When that gambit failed—the NFL owners voted 26-0 with two abstentions to approve Bidwell’s move—Civic Progress remained unwilling to accept the loss of an NFL team. The organization continued to pursue the development of a new stadium as the necessary first step in securing a team. [162]

Charles Knight of Emerson Electric told his Civic Progress colleagues in late March, with the loss of the Cardinals inescapable, that he “had devoted a tremendous amount of effort, as a representative of Civic Progress, in trying to line up a professional football team franchise for St. Louis.” Knight went on, “we do not have a football team and we do not have a consensus among our political leaders regarding the construction of a new stadium.” Absent some form of agreement between the city and county, and a fiscal commit- ment from the state government, there was little likelihood of actually building a new stadium. [163]

Charles Knight told the group, “If St. Louis had a stadium, we could get an NFL team. Built as part of the Cervantes Convention Center, a new domed stadium would give St. Louis the fourth largest convention center in the United States. Additional convention business would bring more new money to St. Louis than the revenues from professional football. However, St. Louis will not be perceived as a big league city until it has a modern football stadium and an NFL team.”

Civic Progress was fully committed to keeping St. Louis an NFL city. The group was equally committed to seeing a new stadium downtown, built and operated as a part of a larger convention complex. So too was Vince Schoemehl. But for County Executive McNary, the prospect of a downtown stadium offered nothing to the suburban county, except as a bargaining chip. McNary continued to promote the idea of a less expensive, open air stadium at the suburban Riverport site. He addressed a letter to St. Louis leaders in May 1988, saying, “I find it amazing that the same Mayor who drove the football Cardinals to Phoenix can continue to undermine our efforts to move this community into the next century.” And he continued his fight with Schoemehl in public, arguing in a June 1988 newspaper article, “Downtown is a very important part of St. Louis but not all of St. Louis.” [164]

As McNary was promoting his stadium, Vince Schoemehl was moving ahead with the plans for the expanded Cervantes Convention Center. Denny Coleman, the city’s economic development head, outlined the effort to Civic Progress in July, stressing (in language underlined in the meeting minutes), “The southern expansion provides additional room for a stadium, should one be built.” But Coleman emphasized that the expanded center “should have a positive impact on Washington Avenue,” where efforts to renew the old ware- houses and industrial lofts had “slowed in recent months . . . . However, the announcement of plans to expand the center to the south has already created a renewed interest in investing in this area.” [165]

Just as Leif Svedrup and the Civic Progress leadership had pressed for the north side site for the convention center originally, Coleman and Schoemehl considered its expansion as a crucial element in bolstering the renewal of the Washington Avenue corridor, and supporting the nearby St. Louis Centre mall as well.

Yet the larger commitment of the Civic Progress leaders was evident in a question from William Cornelius of Union Electric, asking about the possibility of an adjacent stadium. In response (again underlined), “Mayor Schoemehl said that if such a stadium is ever constructed it would make the St. Louis Convention Center the fourth largest facility in the nation. When present plans are implemented, it will be the 10th largest.”

Neither Civic Progress nor Mayor Schoemehl was willing to abandon plans for a domed stadium attached to the convention center. For County Executive McNary, the lack of a football tenant made any form of private stadium financing effectively impossible. Public financing meant that he had to secure approval from the state legislature to raise the county’s hotel tax. There, the opposition of the Civic Progress business leaders could make all the difference.

Gene McNary admitted defeat at the January 23, 1989, Civic Progress meeting, and more publicly the following month. After bowing out of the stadium fight, McNary shortly bowed out of St. Louis, with a presidential appointment as commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, announced in May 1989. [166]

New state legislation for a regional sports facility authority, backed by city, county, and state financing, moved quickly through the legislature in the first months of 1989, greased by the inclusion of language providing state funding for a convention center expansion in Kansas City. But it ran into a political problem with Governor John Ashcroft. The governor took a dim view of the lack of a revenue source for the state debt and the argument that the stadium would generate a “net fiscal benefit,” primarily by attracting larger conventions to St. Louis. Still, faced with what the Post-Dispatch would later term “intense lobbying from business and civic leaders from the state’s three met- ropolitan areas. . . . some very important people wanted this, no matter what,” Ashcroft signed the bill, providing state funds for half the cost of the new St. Louis stadium, in mid-July. [167]

The balance of the roughly $120 million cost for the new downtown dome was to be divided evenly between the city and county governments. With the departure of Gene McNary, H. C. Milford was appointed county executive, and he quickly moved to reassure the Civic Progress leaders of his commitment to the downtown stadium, telling the group in November that the new football stadium was among his “first priorities.” [168]

Milford’s active support was vital to the stadium project, even with the commitment from the state. The county’s one-quarter share of the project needed a new revenue source, and that hotel tax increase had to be approved by a majority of the county voters. Civic Progress made victory in the April 1990 tax vote a central priority, backing the campaign with a contribution of over $400,000. The result was a 65 to 35 percent success.

The city government chose a very different fiscal path from the county’s. Schoemehl had already succeeded—barely—in boosting hotel and restaurant taxes to pay for the expansion of the Cervantes Center. Local hoteliers and restaurateurs were notably cool to the idea of more taxes. In advance of the county tax vote, the lawyer for the local hotel association sought some assurance about the city’s hotel tax. Chief of staff Milton Svetanics wrote a memo to Schoemehl in December 1989, outlining the association’s concerns and his response that “our position had not changed . . . . We expect the new fiscal benefit to be sufficient to meet the needs of the bonds . . . .We do not intend to seek a hotel tax, since we don’t think we’ll need it.” [169]

City comptroller Virvus Jones pressed Schoemehl to commit to a new or increased tax for the stadium bonds, a conflict that played out in public through 1991 and into 1992. But, faced with continuing opposition from hotel and restaurant owners, city officials ultimately chose to avoid the voters and assume that the “fiscal benefit” from the stadium and convention center would suffice to repay the bonds. [170]

The expanded Cervantes Convention Center opened for business in May 1993. Center director Bruce Sommer boasted, “we can now go after bigger groups . . . . But the more important reason for the expansion was to allow us to have simultaneous, mid-sized shows.” And the general manager of the St. Louis Centre mall just to the south said, “We’re expecting a 15 to 20 percent increase in traffic . . . and a large increase in business.” [171]

The expanded center was joined by the new stadium, dubbed the Trans World Dome, in November 1995; the full complex offered a total of 502,000 square feet of exhibit space. In 1988, Mayor Schoemehl had told Civic Prog- ress that the total convention complex would place St. Louis fourth in the ranking of centers. Relying on the Laventhol consultants, he was wrong.

Over the decade it took Schoemehl to realize an expanded center, other cities had been planning and building their own new and expanded convention facilities. Laventhol consultants David Petersen and Charlie Johnson had gone on to other cities—San Diego, Atlanta, and Cincinnati for Petersen; Chicago, Charlotte, and Austin for Johnson—and recommended more convention center space there as well.

When the center/stadium fully opened in late 1995, Tradeshow Week ranked it twentieth among U.S. convention centers. That put it below such cities as Detroit, Dallas, and San Diego, and roughly equal to Kansas City, Houston, and Tulsa. Far from being in the lead as a major meeting destination, St.Louis was competing with a host of other cities. Indeed, the expanded convention complex yielded far fewer convention attendees than the Laventhol consultants had predicted.

There were other competitive problems as well. In 1989, another Laventhol study had argued that the expanded center required a major adjacent headquarters hotel with circa 1,100 rooms. But despite repeated efforts over almost a decade, the city could not find a private developer to invest in a hotel. Finally, in 1999, city officials came up with a financing scheme that involved pairing $98 million in federal Empowerment Zone bonds and other public funds with a small amount of private capital to turn two historic buildings into the new headquarters hotel. [172]

The new Renaissance Grand hotel opened in February 2003. But with the America’s Center underperforming, the new hotel struggled (and usually failed) to earn an operating profit and pay its debts. In February 2009, the bondholders foreclosed on the hotel. Still, with the America’s Center drawing even more poorly in the wake of the recession, the hotel managed an occu- pancy rate of just 52 percent in 2010, with an operating loss—before debt service—of $420,000.

Vince Schoemehl’s vision of conventions as an economic engine boosting the city’s overall economy and creating a flood of new jobs proved an abject failure. And many of the downtown projects that had pressed Schoemehl to fill their new hotel rooms and boost their business were proving failures as well. Fred Kummer’s Adam’s Mark hotel, originally supported by a federal Urban Development Action Grant and intended to be the city’s convention headquarters hotel before the Renaissance, saw dropping occupancy after 2000 and was finally sold, cheaply, in early 2008. The St. Louis Centre mall, where managers had pinned their hopes on the prospect of new convention- eers, struggled through the 1990s as major national retailers left and vacancies grew, and was bought out of foreclosure in 2004 “for the bargain basement price of $5.4 million.” Two years later, it was empty and was poised for rebuilding as apartments and a parking garage, and yet another hotel. [173]

Civic Progress had neatly succeeded in getting both the new stadium and the NFL football team (the Rams from Los Angeles) that it so wanted, along with other projects aimed at redeeming downtown. Whether those “suc- cesses” had indeed succeeded in keeping St. Louis—the city’s population having fallen from 453,085 in 1980 to 319,294 in 2010—a “big league city” is open to question.

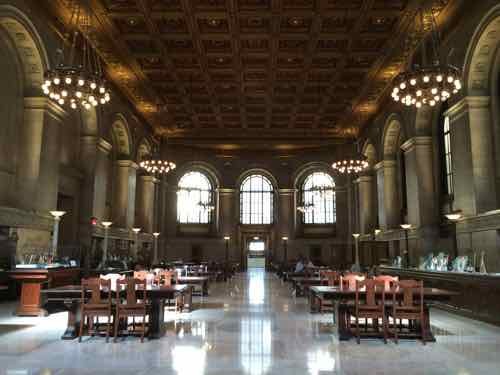

The entire book is recommended, especially all of chapter 8 on St. Louis. Unfortunately neither the St. Louis Public Library or St. Louis County Library list it in their catalogs. It can be ordered through Left Bank Books, Amazon, etc.