A Look at 207 North Sixth Street, Charlie Gitto’s Pasta House Since 1978

When I first saw Charlie Gitto’s restaurant at 207 North 6th Street many years ago I imagined a small business owner fighting Famous-Barr department store parent company, The May Department Stores Company, to keep its small downtown restaurant open.

Sounds good, right? But it was way off.

My first clue was from the recent announcement that Charlie Gitto had died.

Gitto and his wife, Annie, at one point operated as many as six restaurants in the area along with their children.

The couple opened the well-known Charlie Gitto’s Pasta House on Sixth Street downtown in 1978. Their children owned the other restaurants. (Post-Dispatch)

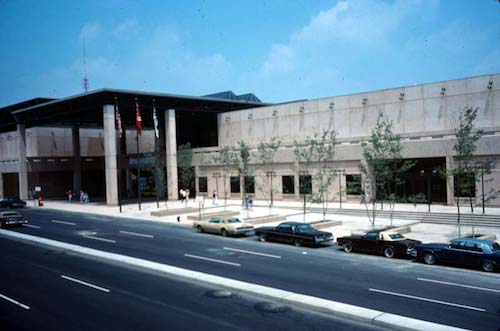

Wait, 1978? The surrounding parking garage was older than that. Though I’d only eaten there once, it looked like it had been there for generations, memorabilia covered the walls. 1978.

So what restaurant was there when the building survived most of the block being razed for Famous-Barr’s parking garage. Was there a fight to keep the small building at 207 N 6th from becoming rubble?

When I decided to seek answers to these questions I had no idea the huge wormhole I was going down. But that’s often the case, especially when searching Post-Dispatch archives.

Before delving into the archives I did a quick Google search. There I found a May 2013 article about how Macy’s planned to close the downtown location in August. It began with this about opening a parking garage:

In September 1922, Famous-Barr proudly opened a new two-story parking garage on Seventh Street, near its bustling department store. It cost $200,000 to build and could hold 400 machines, as cars were known then. (Post-Dispatch).

Wait, 1922? Two-stories?

Instead of quickly finding answers I was finding more questions. I ended up using newspaper archives through the library, historicaerials.com, and Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. City records online weren’t helpful because they didn’t list an age for 207 North 6th Street.

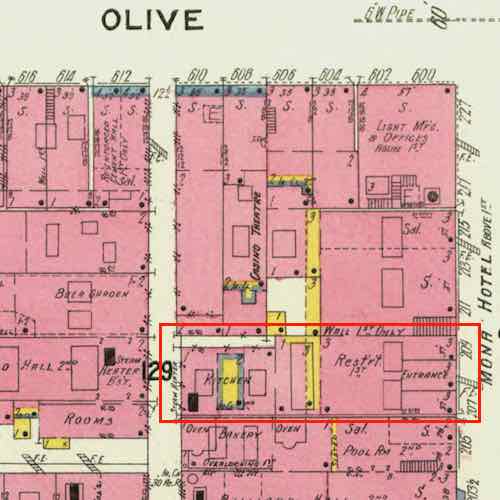

Let’s look at what I found in chronological order, starting in 1909.

So this confirms the site has always been a restaurant, right? Wrong. It was in 1909 and since 1978 but that doesn’t explain which its block got razed.

On January 31, 1922 came the following was on page 3 of the Post-Dispatch:

The Famous & Barr store has purchased, subject to title, the east half of the block on Seventh, between Walnut and Elm Streets, as the site for a four-story or six-story free parking garage for its customers, to be operated on a plan similar to the four-story parking garage that is to be erected by the Scruggs-Vandervort-Barney Dry Goods Co. on the south side of St. Charles, between Eleventh and Twelfths streets.

So in the 1920s both downtown department stores built parking garages blocks from their stores. The site of this first Famous-Barr garage later became part of the 1966 Busch Stadium and is now surface parking at Ballpark Village.

In the final edition of the Post-Dispatch on November 1, 1960 came front page announcement of a new garage, which continued on page 6.

Famous-Barr Co. will raze most of the buildings in the block across Olive Street from its downtown store and will construct a parking garage for 800 automobiles there, Stanley J. Goodman, general manager, announced today.

The 10-level garage will occupy the western half of the block bounded by Sixth, Seventh, Olive and Pine streets. Express exit ramps paralleling Pine street will occupy some of the eastern portion of the block.

The only present stores that will remain in the block are Boyd’s at 600 Olive, Jarman shoe store at 622 Olive and Neels Drug at 207 North Sixth.

So no battle to save the 207 N 6th St building, also that hasn’t always been a restaurant.

On October 11, 1950 Neels Drugs was located at 521 Pine Street. By October 22, 1959 Needs Drugs, an independent Rexall druggist was located at 207 North 6th Street.

On November 27, 1974 Post-Dispatch restaurant writer Joe Pollack indicated, on page 86, that Rich & Charlie’s was going to open another pasta house…on 6th. The very next month there’s a classified ad run December 27-30 seeking dishwashers & porters — apply at Pasta House Co. 207 N. 6th.

In October 1975 Pasta House Company has a location at Plaza Frontenac, but 6 months earlier Rich & Charlie’s was advertising for cooks, dishwashers, etc at Plaza Frontenac. Rich & Charlie’s began in 1967 at 8213 Delmar, a longtime Pasta House Company address. Another article described The Pasta House Company as a “affiliate” of Rich & Charlie’s. Even now I don’t fully understand how these businesses were connected, neither mentions the other on their current websites.

At approximately age 40-41 Charlie Gitto was the manager of the Pasta House Co. chain’s location at 207 N. 6th Street. In 1978 he went from manager to owner of this location, now called Charlie Gitto’s Pasta House. Another pasta house was nearby, Tony’s Pasta House.

— Steve Patterson