We Must Ask Different Questions Before Expanding Our Convention Center

St. Louis is again considering keeping up with the Joneses:

The city’s convention center complex should expand to more than 900,000 square feet, half again its current size, according to a report given Thursday to the St. Louis Convention & Visitors Commission.

Such improvements would bring a “minimum” 37 percent increase in additional business and would position the downtown neighborhood “to re-energize and redevelop,” the report concluded. (Post-Dispatch)

So many red flags in this quote. I’m always suspicious about reports promising increased business — especially that conventions will energize downtown. That’s what they said of the Old Post Office parking garage that replaced the historic Century Building over a decade ago! We should have the promised 24/7 downtown by now.

In the mid-1960s Mayor Cervantes (1965-1973) had backed an existing plan to build a convention center West of Union Station, serving less than 75 trains per day by then. Other business leaders wanted to raze the Old Post Office and they wanted a barrier to the North to hide the 1952 Cochran Gardens public housing — which was built to clear “slums”. They pushed their own plan — in conflict with the new mayor. They didn’t get to raze the Old Post Office, but they did get to create a physical barrier between public housing and the central business district. However, a 1968 study showed the near north location would perform poorly compared to the Union Station site and another location being considered:

The bulky study that ERA delivered to the city in May 1968 concluded, “the addition of a modern convention center is both appropriate and eco- nomical,” attracting annual attendance of 518,000 (including 386,000 at conventions and tradeshows) and generating 192,000 new hotel room nights in the city every year.

Yet where the ERA assessment was quite positive about the promise of a new convention center, it also argued that the site of the proposed facility would be critical to its achieving its potential. The ERA analysis was quite direct (and prescient) in arguing that, while “a convention center can play an important role in stimulating nearby commercial development . . . construc- tion of a single building regardless of its ancillary economic benefits, seldom stimulates downtown revitalization to any great extent.”

The study examined three possible sites. A civic center location, with proximity to hotels, ample parking, and an excellent environment would yield a net annual income of $71,000. A Union Station location, at a greater distance from the center of the core, would generate a net income of $20,000. The third site, the north side, was far and away the most problematic. While the location was convenient to existing hotels, the ERA conclusion was that a center built there “would operate at a serious disadvantage.” The problem was that the location was a “marginal environment,” filled with “one-, two-, and three-story retail stores in a generally deteriorated condition.” With greater likelihood of traffic congestion, the “North Side location would seriously curtail convention center use by local residents and by conventions.” A center there would attract half the annual convention and local events of an alterna- tive site, generating far less attendance and an annual loss. (Convention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American Cities by Heywood T. Sanders)

The success of a convention center didn’t matter — they wanted it to form a physical barrier:

For Sverdrup and for Civic Progress, the new Busch Stadium and the proposed convention center served purposes far beyond baseball games or association meetings. Both major public projects were viewed as changing the physical environment of the core area’s fringe, and as spurs to new private investment.

As a wall, the bulk of a massive convention center could literally shut off the business district and the big department stores from the public housing projects and “cancerous” slums to the immediate north. The entrance to the new center would face south, focused on the downtown core, bringing convention attendees from nearby hotels and restaurants. To the north would be blank walls and loading docks facing the land cleared with federal urban renewal funds. (same)

They worked/fudged the numbers and finally got the public to pay for it:

The formal assessment by Disney’s “numbers man,” Buzz Price, that one downtown official termed “very optimistic,” amply sustained the notion that millions of visitors and attendees would flock to downtown. Price’s imprimatur on the Riverfront Square project thus neatly validated the judgment of Sverdrup and the Civic Progress leadership—St. Louis was on the verge of becoming a major visitor destination. When Mayor Cervantes’s Spanish Pavilion plan was hatched, it neatly followed both the model of Riverfront Square and its location. And the premise of the 1966 ERA study of the pavil- ion was that “Millions of local residents and tourists will be attracted” to the Arch, and that the new stadium would draw “Hundreds of thousands of persons . . . many of them from 100 to 200 miles away.”

Buzz Price’s positive assessment of the Spanish Pavilion was reinforced by the Disney connection. In turn, the forecast numbers from Price and Economics Research Associates for the Pavilion’s attendance and revenues bulwarked the sense among the Civic Progress members that the downtown would see a flood of new people and economic activity. When the possibility of de- veloping a major new convention facility surfaced in 1966, the experience of Chicago, Boston, and San Diego appeared to validate the potential of a center. And once again, the assessment by ERA provided a seemingly expert and reliable forecast of the likely performance and attendance of a new convention center.

ERA’s estimates of the performance of a new center were indeed viewed as so reliable by the St. Louis business leadership that Sverdrup and his firm’s staff simply appropriated them—verbatim—for their own analyses and for the formal presentation of the Convention Plaza redevelopment plan. It was the seeming credibility of ERA, Buzz Price, and project manager Fred Cochrane, as well as the firm’s connections and reputation within the theme park industry, that sustained Mayor Cervantes’s extended commitment to the Union Station site.

St. Louis’s downtown revitalization plans were thus based on the expert judgments of the “best and the brightest” in the planning and economic analysis world. Yet the city’s business leaders were not entirely devoted to following the consultants’ recommendations. When Fred Cochrane of ERA repeatedly warned against building a convention center on a north side site, the interests and goals of a unified business leadership simply overrode his conclusion. For the members of Civic Progress and their colleagues, the interests and concerns of “Cubby” Baer, Donald Lasater, Leif Sverdrup, and the Edison brothers fully trumped outside expert advice. The new convention center was far more about “protection from erosion” than potential as a meeting venue. (same)

The Spanish Pavilion was a huge flop — less than a quarter of projected traffic. It closed within a year. Basically, we built a convention center at the location we were told would perform poorly because influential business leaders selfishly wanted it there to protect their nearby interests.

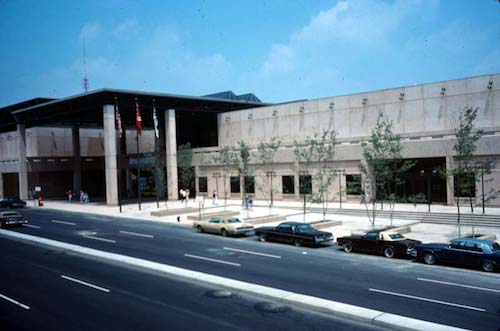

The new Cervantes Convention Center occupied four city blocks — closing 8th St & Dr. King Dr. Ninth & 7th streets were open but faced with harsh blank concrete walls for two blocks. The back of the convention center faced North sending the a message “You’re not welcome downtown.” In the early 90s the center was expanded South to Washington Ave and the dome was added to the East — closing 6th & 7th.

We need to be focusing on reconnecting neighborhoods to downtown — not continuing more than a half century of separation.

A 2014 review of Heywood Sanders’ book gives a good overview of the convention center fallacy:

The idea behind convention centers is to bolster the local economy by attracting visitors who would otherwise spend their money elsewhere. The best measure of success is the number of hotel room-nights they generate.

Sanders’ numbers tell the real story. Washington, D.C.’s new convention center was supposed to deliver nearly 730,000 room-nights by 2010; the actual number for that year was less than 275,000. Austin, Texas’ expanded center was supposed to bring 314,000 room-nights by 2005 but produced just 149,000. The 2003 expansion of Portland, Ore.’s convention center was expected to yield between 280,000 and 290,000 room-nights, but the actual number was 127,000 — far less than before the center’s expansion. Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh and Seattle are among other cities that have had similar experiences. The challenge is to find an exception to the rule.

That’s not all. When projects fail and debt service mounts, consultants routinely conclude that the center needs a “headquarters hotel,” which at the very least requires a large public subsidy. Sometimes the lack of developer interest results in the hotel being publicly owned. It’s a classic example of finding yourself in a hole and continuing to dig. (Governing)

The topic of expansion/updates was the subject of the recent Sunday Poll:

Q: Agree or disagree: Our region’s convention center, aka America’s Center, should be expanded to accommodate larger conventions

- Strongly agree 13 [32.5%]

- Agree 3 [7.5%]

- Somewhat agree 4 [10%]

- Neither agree or disagree 2 [5%]

- Somewhat disagree 1 [2.5%]

- Disagree 6 [15%]

- Strongly disagree 9 [22.5%]

- Unsure/No Answer 2 [5%]

Half agree on expansion, but the other half are split. As you’ve likely guessed, if you’re still reading, I’m very skeptical about promises made by convention center consultants. I don’t have an answer for what we should do, only advice to begin asking the right questions.

— Steve Patterson

There is no “good” way to insert a big box (which is what convention centers are) into an urban setting. The best anyone can hope for is choosing a site that backs up to some undesirable use, like a rail yard (Indianapolis) or a freeway (Kansas City). The challenge remains what happens inside and outside. Inside is a controlled environment, with few access points – great for convention goers, not great for the surrounding city. Outside, ideally, there are either many hotel rooms or abundant parking, or both, along with activities that are NOT directly controlled by the convention or the convention center. If you look at the biggies in the business, at 523,000 sq. ft., we’re a loooong ways away from ever “catching up” with them. Regionally, Indianapolis, Nashville and Louisville all have over 1.2 million square feet (more than double!), while the top dozen, nationally, all have more than 2 million square feet, each (and Las Vegas has TWO that are in that group!), and more than four times what we can offer. Locally, even though Branson is less than half the size (220,000 sq. ft.), it’s apparently doing a good job of attracting regional conventions simply because it’s a) new(er), and b) located some place known for entertainment. So, yes, I agree with you, Steve, we need to ask the right questions before we go crazy spending money we don’t have, just trying, futilely, to “keep up with the Jonses”!

And it IS somewhat possible to maintain existing connections – this is what they did they expanded the Colorado Convention Center, maintaining both an existing street and accommodating street-running light rail. Yes, it’s still a big box, but it’s better than what we have here:

https://www.google.com/maps/@39.7417687,-104.9982902,3a,75y,90t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1swUY5qAJCq_OPhX2zxQLadA!2e0!6s%2F%2Fgeo1.ggpht.com%2Fcbk%3Fpanoid%3DwUY5qAJCq_OPhX2zxQLadA%26output%3Dthumbnail%26cb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile.gps%26thumb%3D2%26w%3D203%26h%3D100%26yaw%3D288.78268%26pitch%3D0!7i13312!8i6656

You said it above, Steve: We need to be focusing on reconnecting neighborhoods to downtown — not continuing more than a half century of separation.”

Downtown St . Louis has some of the poorest connections to its neighboring districts of any mid-major city I’ve seen. It exists as an island, discouraging street level exploration and experiences outside of a very small (VERY small) area.

That’s why I’m so disappointed in the plans presented by McKee for the new “Tucker Triangle, and the City’s utter incompetence (or maybe impotence) in dictating better design and use for this important connective piece. I do believe that, as the northside goes, so too shall the city. (Re)Connecting it to downtown in a meaningful, sustainable, and viable way is the first step.

Steve of correct in how careless the city is in handling the pedestrian experience around the convention center and its connectivity to surrounding neighborhoods (zero).

And it is true the McKee Northside proposal, which after four years of sitting the project is supposed to get going by July, too quick for any one in St. Louis to ask questions like “just what in the hell are you trying to do here?, what is the rest of the neighborhood going to look like?” You know, normal questions like those.

Here are some successful cities and how the city government takes the lead in representing the interests of it citizens.

San Francisco

http://sf-planning.org/eight-elements-great-neighborhood

San Francisco uses eight elements of a great neighborhood to help conversations with city residents and and turns into neighborhood planning.

London

http://mycommunity.org.uk

The original Unitary Development Plan which gave developers outlines of strategic goals for the city and individual neighborhoods which has been updated to a Core Strategy that includes mycommunity. The Core Strategy is the governing document for development.

Helsinki

http://www.hel.fi/www/helsinki/en/housing/planning/current/current

This is in English(as is much of their site). This shows an extensive list of traffic and housing planning currently going on, if you click on any of the city locations the text is in Finnish, but you can see the number of maps of districts in the city they are working o and what is going on.

In all cases above the city government is engaged. They are engaged in a proactive manner with the citizens to shape the environment for the betterment of everyone. these are real processes not proposals. And there are plenty more.

St. Louis city officials just wing it. I posted these links at Nextstl on an article about the Hill, yet another project that exhibits all the signs of city neglect of a neighborhood.

City planning: urban design in St. Louis is second rate, third rate, maybe 10th rate, who knows? but yeah the McKee proposal, after what, 4 years of silence, duh,duh, this is all we can figure out says the gang who can’t shoot straight.

It’s past ridiculous at this point.