Historical Background on St. Louis’ Main Post Office

Last month I posted about how the employee line for the main Post Office parking garage was two blocks long — costing workers time & money — and polluting. My point was to find a way to reduce/eliminate this shift-change queue. However, a few comments were classic strawman fallacy — saying I wanted this post office to close — moving the sorting & processing jobs to a suburban. Uh…no. Again, my point was to collectively find a way to get people to their jobs without having to queue up just to park. That said, the USPS might decide to move mail process out of downtown to more modern facilities. If they do — it won’t be because I don’t like the daily queue for the parking garage.

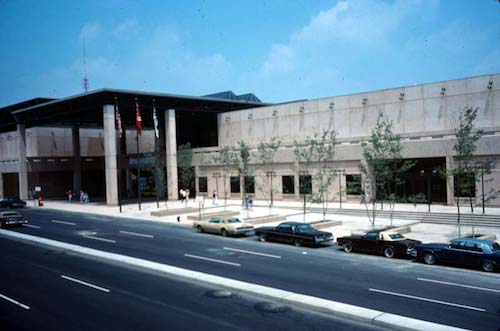

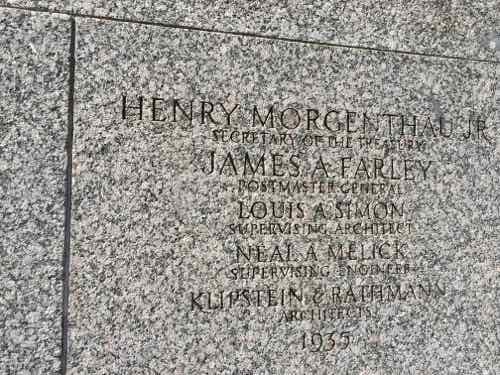

The possibility of the processing moving got me thinking about the history of the Main Post Office on this site. I knew online city records didn’t have the year built, so I’d need to investigate beyond a quick online search. Buildings from this era usually had cornerstones — people weren’t embarrassed to have their names displayed on them for eternity. Though I’d never seen a cornerstone here before, I knew one had to exist.

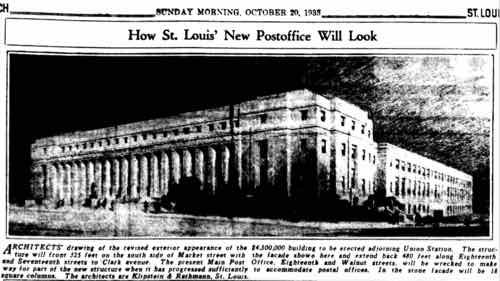

Back home I found online that an article from October 1935 talks about the design. So off to the 3rd floor genealogy department at the Central Library to find it on microfilm. Note: searching Post-Dispatch articles 1874-1922 can be done online through a free database, using your library card account for access.

So we know the Main Post Office in October 1935 was at 18th & Walnut, from the article:

The excavation and foundation work have been completed for some time. It is estimated that it will take 900 calendar days, approximately two and a half years, to complete the superstructure. The architects are Klipstein & Rathmann of St. Louis, Engineers are W. J. Knight & Co, on structure. John D. Falvey on mechanical work and Joseph A. Osborn on electrical work.

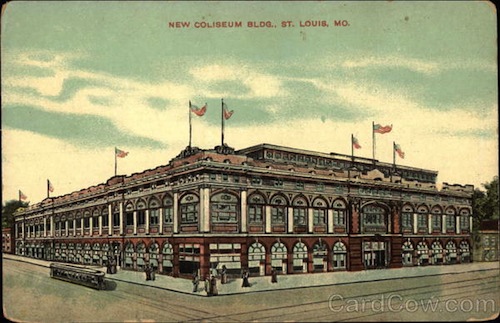

An earlier post office, at 18th & Walnut, was razed to build the present one between 17th-18th. An older post office annex building still exists between the Union Station train shred and 18th Street.

Foundations done for some time? An earlier paragraph explains the delay:

Construction of the superstructure was delayed by the Supreme Court decision on the NRA which necessitated asking for new bids. Representative John J. Cochran of St. Louis has been in constant communication with the procurement division of the Treasury and with the Post Office Department in an effort to speed up the project.

NRA? A different one.

National Recovery Administration (NRA), U.S. government agency established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to stimulate business recovery through fair-practice codes during the Great Depression. The NRA was an essential element in the National Industrial Recovery Act (June 1933), which authorized the president to institute industry-wide codes intended to eliminate unfair trade practices, reduce unemployment, establish minimum wages and maximum hours, and guarantee the right of labour to bargain collectively.

The agency ultimately established 557 basic codes and 208 supplementary codes that affected about 22 million workers. Companies that subscribed to the NRA codes were allowed to display a Blue Eagle emblem, symbolic of cooperation with the NRA. Although the codes were hastily drawn and overly complicated and reflected the interests of big business at the expense of the consumer and small businessman, they nevertheless did improve labour conditions in some industries and also aided the unionization movement. The NRA ended when it was invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1935, but many of its provisions were included in subsequent legislation. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

The National Recovery Administration was created in 1933, but ended on May 27, 1935 when the Supreme Court unanimously interpreted the Commerce Clause differently than Roosevelt in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States.

One more quote from the article:

Besides serving the postal needs of St. Louis, the new building will be a distributing center for all postal supplies, machinery ns equipment for post offices throughout the Southwest.

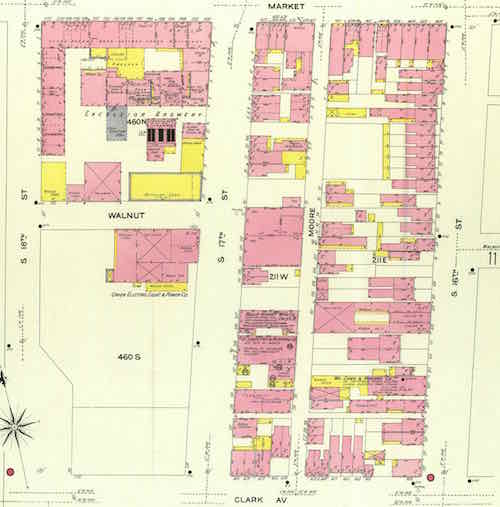

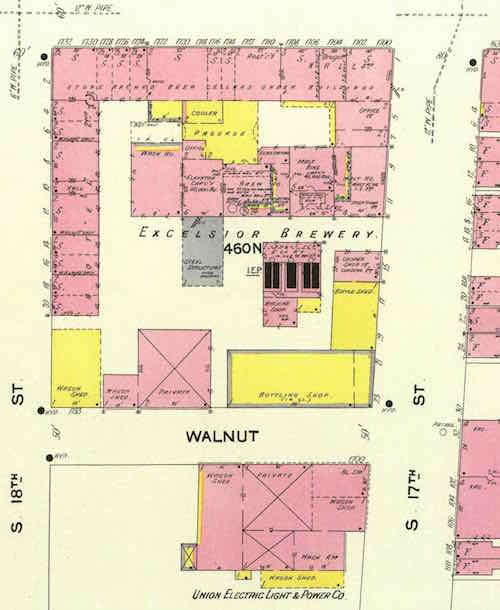

The new post office opened in 1937. so that takes care of the history, right? Not quite. From the 1935 photo caption we know the previous Main Post Office was at 18th & Walnut, but because the current post office Walnut Street doesn’t exist between 16th-18th. So I turned to Sanborn Fire Insurance maps:

The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Company, established in 1867, compiled and published maps of U.S. cities and towns for the fire insurance industry to assess the risk of insuring a particular property. The maps are large scale plans of a city or town drawn at a scale of 50 feet to an inch, offering detailed information on the use made of commercial and industrial buildings, their size, shape and construction material. Some residential areas are also mapped. The maps show location of water mains, fire alarms and fire hydrants. They are color-coded to identify the structure (adobe, frame, brick, stone, iron) of each building.

Between 1955 and 1978, the Library of Congress withdrew duplicate sheets and atlases from their collection and offered them to selected libraries. Maps for Missouri towns and cities were given to the MU Libraries. Documenting the layout of 390 Missouri cities from 1883 to 1951, the University of Missouri-Columbia Ellis Library Special Collections Department has digitized 6,798 of the maps for Missouri cities from 1880 to 1922.This Project is supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act as Administered by the Missouri State Library, a division of the Office of the Secretary of State.

Most of the ones for St. Louis are from 1907-1911.

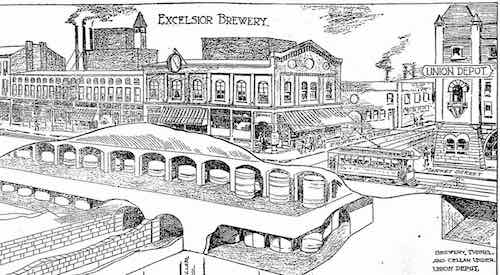

In the block bounded by Market, 17th, Walnut, and 18th is Excelsior Brewery. The only thing South of Walnut is a Union Electric building with vacant land. My unconfirmed assumption was a post office was built after December 1908 o the block South of Walnut. So the new post office replaced the brewery? That was my initial hunch, but it’s far more complicated.

An article from October 21, 1917 has the headline: “$1,000,000 HOTEL PLANNED TO FACE UNION STATION”. The “skyscraper type” hotel would have 450-500 rooms, to be built by someone from Oklahoma. From that article:

The site, which is owned by the St, Louis Brewing Association, will be acquired either under a 99-year lease or by purchase outright. Norman Jones, secretary and treasurer of the brewing association, stated the owners are not interested in the project, but are desirous of leasing the site for improvement with a building of the nature stated. He said the association would either lease or sell the plot, and for that reason it had declined to tie it up with short-term leases. He stated that the association had plans, several years ago, for a large hotel for this plot, but that they had been lost.

The Market street frontage is filled with a conglomeration of small stores, picture theaters and saloons. The rear, or Walnut street side of the block, was occupied by the Excelsior Brewery, the building of which was recently razed.

Several years ago a group of Chicago capitalists head this block under consideration for improvement with a large hotel structure, but the project collapsed when Europe was plunged into war.

This 1917 article says this hotel would be compatible with the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange’s plans for a plaza in the catty-corner block bounded by 18th, Market, 19th, and Chestnut. Side note: that plan eventually doubled in size to 20th, it was fined by a 1923 bond issue. The centerpiece Meeting of the Waters fountain & sculpture were completed in 1939 — two years after the new Post Office opened.

An article from November 11. 1917 says an $800,000 13-story hotel with 700 rooms was to be built on the Northeast corner of 18th & Market.

A brewery previously existed where Union Station was built, this was operated by the Uhrigs — who earlier had opened a beer garden at Jefferson & Washington.

- A Julius Winkelmeyer and Frederich Stifel moved there small operations to 18th & Market in 1846, it was started the year before at Convent & 2nd.

Ok, so both 1917 hotel plans failed, the brewing association sold the Southeast corner years later for the post office? Yes and no, respectively.

Ever since the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis opened Union Station on September 1, 1894, there was an effort to “improve” the appearance of the blocks facing it. Prohibition lasted from 1920-1933. A week ago I found an article suggesting they had bought the Excelsior Brewery property, my assumption is they sold or donated it for the new post office.

At some point I may return to dig more into the history of this intersection, but I’ll stop for now.

— Steve Patterson