Replacing Our Chinatown With A Baseball Stadium Was One Of Many Mistakes

In the 1960s Urban Renewal was in full swing — remaking/destroying cities on a large scale. The majority of people approved — few protested. The powers that be had dismissed Jane Jacobs’ 1961 critique: The Death & Life of Great American Cities.

Forty city blocks of our original city had been vacant for a quarter century when Time magazine wrote the following on July 17, 1964:

In all, some $2 billion worth of major construction is under way or planned in the metropolitan area. A 454-acre midtown tract of slums called Mill Creek Valley, filled with slum housing that cried out for rebuilding in 1954, is now one of the largest urban-renewal areas in the U.S. A substantial section of it will be set aside for an expressway to link downtown with the major expressways leading out of the city. The long neglected riverfront has been cleared for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Park; scheduled for completion there next year is a soaring stainless-steel arch 630 ft. high, designed by the late Eero Saarinen as a monument to St. Louis as Gateway to the West. A seven-block pedestrian mall shaded by trees and flanked by lawns is abuilding. Ground has been broken for a 1,100-car parking garage, first step in construction of a downtown sports stadium, designed by Edward Stone, that will seat 50,000, cost $89 million.

The program has its critics. The Mill Creek slums were bulldozed in 1960, but redevelopment has been so slow that the area is locally dubbed “Hiroshima Flats.” The New York Times’s Ada Louise Huxtable charged that the rebuilders had razed “the heart and history” of the city by clearing the riverfront. Defenders point out that the storied waterfront had long deteriorated into a grimy morass of dilapidated warehouses, buildings and residences. Developers have been scrupulous in preserving the architectural monuments of the area—the old courthouse and the cathedral—and have stored the best examples of cast-iron storefronts to be put on display in the new Museum of Westward Expansion. (Time)

“But these areas were bad, they had to be razed,” you might say. That was the propaganda constantly sold the public. Another such bad area that needed to be razed? The Soulard neighborhood (see 1947 reconstruction plan). Basically if they wanted to remove something a campaign was waged to build public support. Often, there were racial motivations.

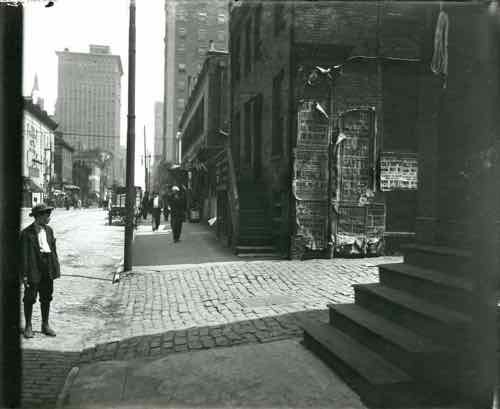

The neighborhood razed for Pruitt-Igoe was Irish. Mill Creek Valley was African-American. And what became Busch Memorial Stadium (1966-2006) had been our Chinatown since the 19th century:

The first recorded Chinese immigrant was a tea merchant named Alla Lee, who is reported to have arrived in 1857 from San Francisco. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese community in St. Louis had grown to about three hundred. This community was physically centered in “Hop Alley,” a seemingly mysterious place that inspired tall tales to the contemporaries and is little known to the present St. Louisans. Along Seventh, Eighth, Market, and Walnut Streets, Chinese hand laundries, merchandise stores, grocery stores, restaurants, and tea shops were lined up to serve Chinese residents and the ethnically diverse larger community of St. Louis, the fourth largest city in the United States at the time.

Downtown businesses wanted the gleaming new modern downtown and Chinese-Americans doing laundry didn’t fit that image. They must go! But how? At this same time those who pushed wholesale razing of large areas knew cultural institutions were a good excuse to raze existing areas — forcing the inhabitants to be relocated. Working with Cardinals owner Anheuser-Busch, the process began to push Chinatown out of downtown. This would also put the team closer to the brewery.

In February 1968 New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote the following about downtown St. Louis:

Except for the arch and the old courthouse, which form some genuinely provocative urban views, downtown St. Louis is a monument to chamber of commerce planning and design. It is a businessman’s dream of redevelopment come true.

There are all the faceless, characterless, scaleless symbols of economic regeneration — luxury apartments, hotels, a 50,000 seat stadium and multiple parking garages for 7,400 cars. Sleek, new, prosperous, stolid and dull, well served by superhighways, the buildings are a collection of familiar profit formulas, uninspired in concept, unvarying in scale, unrelated by any standards, principals or subtleties of planning or urban design. They just stand there. They come round, rectangular, singly and in pairs. Pick your standard commercial cliche.

The new St. Louis is a success economically and a failure urbanistically. It has the impersonal gloss of a promotional brochure. A prime example of the modern landscape of urban alienation, it has gained a lot of real estate and lost a historic city. (“Hop Alley”: Myth and Reality of the St. Louis Chinatown, 1860s-1930s)

Much of downtown remains faceless, characterless, and scaleless. The area where baseball had been played since the 19th century suffered from the loss of jobs & activity. One institution resisted the trend to locate in a modern downtown building, the symphony instead restored an old movie palace. Ada Louise Huxtable again:

The success of Powell Symphony Hall in St. Louis is probably going to lead a lot of people to a lot of wrong conclusions. In a kind of architectural Gresham’s law, the right thing wrongly interpreted usually has more bad than good results.

The first wrong conclusion is that Powell Hall represents the triumph of traditional over modern architecture. False. The correct conclusion here is that a good old building is better than a bad new one. Powell Hall represents the triumph simply of suitable preservation. And, one might add, of rare good sense.

Very rare in St. Louis. We can’t change the past, so why keep harping on it? Because we’ve not learned from our past mistakes! We keep repeating, at least attempt, to repeat them.

Readers were split in the non-scientific Sunday Poll:

Q; Agree or disagree: Building the new baseball stadium downtown in 1966, instead of in a neighborhood, was a bad decision

- Strongly agree 5 [11.63%]

- Agree 6 [13.95%]

- Somewhat agree 9 [20.93%]

- Neither agree or disagree 3 [6.98%]

- Somewhat disagree 4 [9.3%]

- Disagree 9 [20.93%]

- Strongly disagree 6 [13.95%]

- Unsure/No Answer 1 [2.33%]

Those who agreed totaled 46.51%, while those who disagreed totaled 44.18%.

We can’t undo the past mistakes, but the disastrous Urban Renewal mindset is still alive in 2016 St. Louis.

— Steve Patterson

Steve, you’re vastly oversimplifying the history. Taking an academic’s view in the face of day to day pragmatic real problems of fifty years ago is sort of vain.

The problems of Urban Renewal have been well documented, which is part of the reason why it was replaced with block grants.

Downtown urban renewal and replacing the jewelbox ballparks in 19th Century neighborhoods with centrally located multipurpose stadiums were related but distinct phenomena. They clearly intersected here, but not quite in the nice tidy way you’re trying to present it. I think that was the point of the original comment. Even if Gussie and St. Louis hadn’t embraced the prevailing mindset of 1960s renewal and razed Chinatown to do it, the old Yeatman neighborhood was not going to keep a major league ballpark.

I agree with that,,, I don’t think the present location is ideal (but it is better than Busch II by being slammed up against the elevated lanes) but without streetcars or light rail North Grand simply wouldn’t be able to handle the thousands of vehicles. Besides gridlock, there’d have to be an incredible amount of parking garages and/or surface lots around the ballpark. Unfortunately, Saint Louis is no longer like Boston or Chicago that can still sustain a Fenway or Wrigley=style “neighborhood” stadium via strong transportation networks.

Forgot to add that if Busch didn’t go in, the area probably would have been demolished for something else to satiate the thirst for Urban Renewal.

I find an interesting parallel between the rationalization to “rid the city of heathens and aliens” in Hop Alley in the 60s and the current rationalization to “rid the downtown revitalized loft/business district of heathens and aliens” at and around New Life Shelter, both ostensibly to improve the image of STL and to provide cleaner, safer environments for residents and businesses, to eliminate the scenes of vice, corruption…and the poor. On the one hand, it APPEARS that liberals can justify pushing out the poor at NLEC, who urinate and defecate on streets and in alleys and engage openly in sexual activities, and yet they passionately mourn the passing of the Chinese in Hop Alley who reportedly engaged in smoking opium and other activities deemed at the time to be offensive. So what is offensive? Would oral sex, public urination in alleys in Soulard at Mardi Gras be deemed offensive? My family witnessed an encounter of oral sex on our last visit to Soulard at Mardi Gras. But it’s a fairly common scene in Europe, so we continued walking to our destination. Can “this type of behavior” be overlooked, or should Mardi Gras be past tense? Should STL rid the city of the “Neo-pagan, shameful and immoral” acts associated with Mardi Gras, or even somehow FORBID the roaming poor in STL from publicly urinating in a remote alley behind a dumpster by performing a penectomy on all offenders? Or would it be easier and more humane to allow these poor residents to continue living in NLEC, provide restrooms and showers in given areas and, mercifully and with open mind, provide urban dwellers the opportunity to enjoy some of the diversity that urban folks claim to embrace and that cities have characteristically and enthusiastically purportedly supported over the decades? Who am I to say that the homeless (and their ways) should or shouldn’t be allowed to co-exist with the loft dwellers? And who is anyone else to say that the 60s wasn’t a good time to make way for different opportunities for the Hop Alley area? There’s a lot of selective liberalism being thrown around here and I find it amusing–but really not surprising.

….and with 5- and 6-riser (35-46″ min. landing height) stairs shown in your photo and the close proximity of the buildings to the curb , (done probably to avoid the effects of seasonal flooding), what are the odds that accessible entrances could have been cost-effectively constructed at those buildings, without major infill and shoring and sub-surface infrastructural improvements necessary to raise the street elevations, or by constructing so many ramps that the area would have looked like a skate board park, or even by moving recessed entrances inward, even farther from the curbs which would have required extensive internal structural building modifications? Somehow I think the powers-that-were might have made the right decision, this time.

With the clarity of 20/20 hindsight, it’s always easy to find fault. It’s also easy to play the “what if, but only” game, making assumptions on outcomes that might or might not have happened. How about taking everything that we’ve supposedly “learned” and applying to contemporary challenges, like McKee’s plans for north city?

Are you objecting to the loss of a “community” or to the loss of the old buildings? People create “community”, not buildings. Our “Chinatown” is now out along Olive in University City. Our Jewish community (and its synagogues) have moved steadily westward. The Irish moved to better housing as they integrated into society and became more prosperous. We have a huge Bosnian community centered in what was once a Dutch enclave. And this is NOT unique to St. Louis, it’s typical of every major city, where succeeding waves of immigrants redefine neighborhoods and their characters.

As for the old buildings, there are two very distinct issues, the fabric they create and the condition that they’re in at any certain point in time. At some point, most buildings become unsalvageable, with the cost to repair deferred maintenance far exceeding the cost to remove and replace – few things last forever, especially in poorer communities, where ongoing maintenance is usually inadequate. Yes, they/we “should” take better care of old buildings, but many don’t have the financial resources nor the motivation to do so.

That leaves just the urban fabric. As we’ve all seen and all know, cities are constantly changing. The urban fabric reflects those choices and those changes. Yes, it would be great if all of downtown was densely built-out, with no surface parking or large public sports facilities. But since there’s less and less of the former (tenements, small businesses, manufacturing and office users), there will be, by default, more and more of the latter (surface parking, government uses and government-funded uses put in place to “attract” people downtown). If there had been no federal urban renewal program, we would not have seen whole blocks demolished, but we what we would have seen is what’s happened everywhere else in the city. As buildings became/become “obsolete” in their OWNER’S eyes, they’re slowly but steadily being abandoned and/or demolished.

The underlying land and the underlying street grid has not changed all that much, just the willingness of OWNERS to invest in their properties in the way you see as best for the larger community. We get new QuikTrips instead of new “urban” mixed-use buildings not because of any failing of political will, but because QT’s make a lot of money! It’s a business model that fits contemporary times, just like BPV, Busch III and the Scottrade Center do. What worked 75 or 100 years ago isn’t all that relevant to most people TODAY. And what will be the “right” answer in 2050 or 2100 will likely be a different answer than today’s or those from 1990 or 1960. Yes we can certainly “learn” from the past, but just repeating it, down to the smallest detail, is no answer for a world of computers and solar energy, not a world of streetcars and the telegraph.

I share your view point. American Cities in general have been eager to shed old buildings and communities in favor of highways, parking garages and gas stations. We repeatedly end up disappointed in the results but surprisingly cannot make the connections that we are dealing largely with the consequences of bad planning decisions. If we can’t even acknowledge this, we are unlikely to change our ways.

Oh, c’mon. We are changing our ways. Look at the Grove, Cortex, and the Central corridor. People are flocking to areas with tech jobs, walkability, public transit, and urbanity. Especially Millenials. A young, educated workforce doesn’t want to live in vanilla suburbia anymore. They want to live in cities. What St. Louis needs to do is leverage the growth of the Central Corridor into neighboring areas. And we’re doing that, too. You guys need to quit with the Debbie Downer retrospectives and focus on what’s happening now. It’s all about restoring density. Federal Mogul is going to take an abandoned industrial area in the heart of the city and turn it into a many-million dollar ($100 million plus?) mixed use development, further extending the growth around Cortex and Grove.

We also tried to race an area with occupied buildings & historic districts for a tax-payer funded stadium while we still owe on the last stadium we built. We’re looking at erasing an area across the street from the old Pruitt-Igoe site — which has been vacant for 4 decades — to build a high security fortress.

Re. the N. Riverfront: In an area where it looks dead and deserted. No stadium happened. What now?

Re. NGA: And keeping 3,000 plus jobs in the city (maybe up to 5,000).

The larger problem with the Rams is that they didn’t want to stay here, and neither did the NFL especially want them to remain. As Kroenke was a disliked and mediocre owner anyway, I think the wiser choice was to just let them go.

Yes, NGA is a plus. I see no downside to putting a facility that will employ so many people into an area that is essentially nothing but blight. There will be a consequent loss of access to the area, as well as closure of some through-streets, but I think that’s a very small price to pay. Historically, new projects in big cities have often been built in areas generally viewed as rundown and crummy; such was the case in the building of the World Trade Center in New York in the 1960’s; obviously, this is also why the Arch exists in the particular area it is located in. I tend to think that overall, these were both relatively good projects, but outstanding buildings have also been lost here and in other cities in similar circumstances. Those types of losses need to be continually guarded against.

I think the present location of the baseball stadium downtown next to the freeway and Metrolink is essentially ideal. My own view is that the downtown would have become even more rundown and blighted during the bad years without the presence of the Cardinals to help hold things together. Also, part of the reason for the new stadium being built downtown in the 60’s was to keep the football Cardinals here, who were threatening to move elsewhere. As other cities were also planning or building multipurpose stadiums at the same time, mostly in downtown locations, Busch Memorial Stadium fit in well with that trend and did help keep the football team here another 20 years. In contrast, the building of the dome to lure the Rams did not really work out very well. We are stuck with a huge and undesirable white elephant that is still not paid off, with no team left to play in it, and no team that would want to move here to play in it. I have no solution to offer to that particular problem.

I wouldn’t be popping the champagne corks yet. Ikea is a pedestrian disaster at Cortex. The pedestrian and transit user have the same walk as a person parking furthest from the store, even if the lot is empty. Talk is cheap, the results of Cortex look promising but time will tell if it is well done.

You also have McKee on the North side proposing autocentric designs.

You also have Aldis who wants to rebuild its store on South Grand. It is another autocentric design.

These are happening now.

I have looked at many projects over the years. I would say city governance is far, far from the point when walkability, public transit and urbanity concerns show up in the design of the city on any kind of regular basis.

The Debbie Downer retrospectives will cease when there is real, not imaginary progress in creating environments for pedestrians. An obsessive reverence of the auto is the norm right now.

Check out the East West Gateway 2045 transportation plan, it is all about the auto and maintaining the status quo for the next 3 decades.

Aldi’s and McKee want to build autocentric projects because that’s where the market for new developments currently is! There is no lack of old, “urban”, small-scale, fine-grained commercial and residential structures throughout the city, for those businesses and residents who want them. It boils down to basic supply and demand, not to any lack of political will or city governance. The city can’t force private property owners to spend money on projects that they view as unprofitable. The city can offer incentives, the city can offer tax credits, the city can even write zoning language to “steer” developments in the “correct” direction, but they can’t force owners or developers to build something they don’t WANT to build! Density happens when it makes financial sense, not when some bureaucrat or group of interested citizens demand it!

Site planning that meets pedestrian needs also does not impact the automobile to any great degree. Clearly you do not understand the need for continuity in city building. Disruption of the pedestrian experience by poorly sited parking is all over St. Louis.

So yes the city government has a duty to insure equal access for pedestrians through regulations and policy. In addition, most of these projects recieve public money through TIF, abatements and so on giving the city all the more reason to make sure the projects are pedestrian orientated.

I have mentioned to you before that your line of thinking has been in place for the last 60 years and it is a proven failure.

I also don’t think you really understand supply and demand and how it works, you invoke it all the time as if it is some mystical truth.

There is absolutely no reason the environment cannot accommodate the pedestrian as well as the auto. It is a matter of will, not money.

Well said, JZ71 epitomizes everything that is wrong with St. Louis for decades. He, like so many, can’t see it. Probably never will.