2011: MetroBus Growth Rate Double MetroLink

Ridership on the region’s bus service (MetroBus) grew at more than twice the rate of the region’s light rail service (MetroLink), according to figures in a new report by the American Public Transportation Association. Looking at 2011 compared to 2010 the light rail service increased ridership a below average 4.62% while bus ridership increased a whooping 10.04%, way above average for the report.

APTA reported large bus systems like MetroBus in St. Louis grew by 0.4 percent nationally. Columbus, Ohio at 10.1 percent showed the strongest bus ridership growth in the nation while St. Louis at 10 percent experienced the second largest growth, and Orlando, Florida at 8.4 percent, the third strongest bus ridership growth in the nation. (Metro Press Release)

Outstanding!

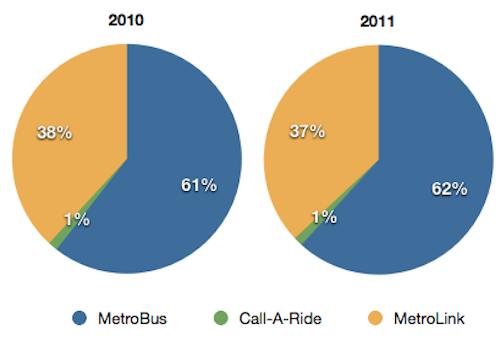

As a result of the substantial increase the humble bus is carrying an even greater percentage of the region’s transit riders. MetroBus carried 61% of Metro’s passengers in 2010 but that increased to 62% for 2011. Conversely the light rail service dropped from 38% to 37% from 2010 to 2011, see pie charts below.

It’s no wonder since MetroBus service covers so much more of the metropolitan area. MetroBus likely has a stop near your home and work/school whereas light rail isn’t as convenient. I can catch three different MetroBus lines within a block of my house (3min) but the nearest MetroLink station is 12 minutes away! Sure the MetroLink is faster than MetroBus but when I factor in time getting to/from each mode the bus usually wins if both are a choice.

Some will point out that MetroLink has a higher farebox recovery than MetroBus (27.8% vs 19.9%; source page viii). True enough, but MetroBus covered 5.7 times as many “revenue miles” as MetroLink in FY2011 (18,198,927 vs 3,147,407; same source). Naturally bus service isn’t going to have the same farebox recovery rate given how much of the region the service covers — those routes to low density areas just aren’t as efficient as other routes. We could never afford to provide light rail service to all parts of the region now served by bus.

St. Louis bus & rail ridership was down in 2011 from what it was in 2008, but current gas prices might push ridership levels for 2012.

– Steve Patterson

Transit can serve one of two possible audiences (or both): the “transit captive” and “everyone else”. The first category don’t own cars or don’t have driver’s licenses. The second category does. The first category will take transit no matter how inconvenient it is because they have no alternative. The second category will take transit only if the level of service is comparable to driving (in terms of speed, frequency, comfort, etc.).

In low-density areas, providing a transit service comparable to driving is simply unaffordable. MetroBus covers a huge area, but much of that area only receives a bus every half-hour to hour, and the buses are slow relative to cars (no freeways). Taking a bus in St Louis County you will quickly see that many of the riders are City residents commuting to low-level jobs in the suburbs. Everyone else in the County drives instead. MetroLink, in contrast, is much faster, is more frequent than almost all bus routes, and is generally thought of as more comfortable. On the limited routes that it travels it *is* comparable to driving, and many non-transit-captive people take it as a result.

If you are interested in increasing density and promoting urbanism, you need to involve the non-transit-captive. The transit-captive are already taking transit and always have been. But there are not enough of them, and they don’t have enough investment capital, to make urbanism viable. Providing buses to distant locations for the transit captive is worthwhile morally and economically, but does little for urbanism.

I understand that currently MetroLink provides little for City residents (it reaches just one City residential neighborhood – CWE). That is why the next planned light rail line is Northside-Southside. It has the potential to promote dense redevelopment in the City in a way the current bus system does not. In theory a BRT line with separate right of way and efficient fare collection could accomplish much the same as a rail line (at a somewhat comparable cost), but for some reason no serious proposal for BRT in St Louis has ever been put forward.

I agree with your first three paragraphs, with one exception – there are actually three groups, not two. The choice group includes daily commuters and the occasional riders who use transit just to go to special events. Their transit needs are completely different, and require different responses from Bi-State/Metro. Meeting their needs, however, is critical to Metro’s success since they’re also taxpayers. As Steve notes, less than 30% of any trip’s cost is covered by fares, the rest comes from local sales taxes and federal grants, both of which rely on ALL taxpyers, not just those who ride transit.

I never agreed with the Record of Decision / Preferred Alternative for the Northside-Southside study. Light rail will NOT be the economic generator everyone wants in this corridor, while other technologies would be a much better fit, be they streetcars, BRT or just increased frequencies using larger, articulated buses. Light rail does nothing to enhance development between stations, and to function well, stations need to be at least a mile apart. Add in the disruption to just build the system (several years of serious road closures) and you’ll kill more businesses than you’ll develop.

I disagree with your statement that “currently MetroLink provides little for City residents (it reaches just one City residential neighborhood – CWE).” THe Shrewsbury station is located in the city and serves the surounding neighborhoods (LIndenwood Park and St. Louis Hills). The Forest Park station serves the DeBalivere neighborhood, the Grand station serves SLU and its students and the downtown stations serve parts of the loft district.

I also disagree with your statement “That is why the next planned light rail line is Northside-Southside.” Just because a study is complete does not make it “next”. East-West Gateway COG is the group that will actually decide which line is next, based on regional needs and, unfortunately, politics. My understanding is that a northwest line is probably the most likely one, out to West Port.

“Light rail does nothing to enhance development between stations, and to function well, stations need to be at least a mile apart.”

So wait you said a few post back that streetcars are not good for economic development because stops are too close together and thus don’t move people quickly enough? So which is it?

“Add in the disruption to just build the system (several years of serious road closures) and you’ll kill more businesses than you’ll develop.”

We worked with I-64 shut down?

Question one – both. Buses and streetcars function virtually the same way, operating in city traffic with stops every few blocks. Streetcars are cuter and since they have a fixed guideway (rails) they do tend to attract some additional riders and some additional development investments, but at a higher cost than just deploying bus service. It all boils down to a cost-benefit analysis.

Question two – no businesses directly faced I-64,nor Forest Park Parkway, for Metrolink’s most recent project, access was available from surface streets. Logistically, building light rail on Grand would require rebuilding much of the subsurface infrastructure (to get it out from under the rail corridor), while, in my understanding, streetcar tracks can be laid on top of old water and sewer lines. Streetcar line have been built one block at a time, closing streets for as little as a month. Light rail lines typically take several years to complete, especially on urban streets, which could easily destroy the fragile business infrastructure on North Grand.

The real challenge / problem with the Northside-Southside study is an unclear focus. Is it supposed to improve local bus service or is it supposed to move commuters over longer distances? If the answers are both objectives and rail, the only way to make things work would be to install 3 or 4 sets of tracks, not just two. Longer-distance, express service needs to get around stopped local service, and three tracks would create an “express lane” (like I-70), while 4 tracks would allow true two-way, dual levels of service. That’s why I believe that enhanced bus service offers a much better option.

“If

you are interested in increasing density and promoting urbanism, you need to

involve the non-transit-captive.”

Getting

higher income people to use transit is important when the system needs to

expand as that creates a group of voters willing to tax themselves. Yet where

in Saint Louis do we have proof of urbanism increasing with light rail? What

stations have implemented TOD? Rather than spurring development we only see

large park and ride lots. Yes, getting people out of their cars and using light

rail is good for the environment, but I don’t see any evidence of changes in

land use resulting from Metrolink.

“Taking

a bus in St Louis County you will quickly see that many of the riders are City

residents commuting to low-level jobs in the suburbs.”

This

speaks to a larger problem which transit, at least at its current level, does a

poor job at addressing: spatial mismatch. As long as suburban and exurban areas

are able to prevent the construction of affordable housing these busses will be

necessary. That is insofar as Chesterfield shoppers want their stores open yet

not live next to the people who sell them those goods and services.

Sounds like you’re playing a numbers game, using statistics selectively to illustrate a desired conclusion. Big picture, in prior years, bus service was cut more than light rail service, thus it would stand to reason that bus ridership would increase more than light rail ridership, once the bus routes were restored to their previous levels. The good news is that ridership, overall, is increasing.

You state “Naturally bus service isn’t going to have the same farebox recovery rate given how much of the region the service covers — those routes to low density areas just aren’t as efficient as other routes. We could never afford to provide light rail service to all parts of the region now served by bus.” This gets to the heart of transit economics, balancing revenues and service. To be fair, there should be no assumption that “Naturally bus service isn’t going to have the same farebox recovery rate”. What really needs to be looked at is much finer-grained. Every segment of every route needs to be documented and analyzed as to its efficiency (and I’m pretty sure that Metro is already doing so), whether it’s bus or rail. We need to get the most bang for our buck, especially that 70%+ that comes from general tax revenues.

If “those routes to low density areas just aren’t as efficient as other routes”, then we need to look at other options. Denver has been successful in suburban areas moving away from low-productivity fixed routes to call-n-ride service for all customers, somewhat similar to the call-a-ride service Metro offers the disabled community here. They operate within fixed boundaries, usually centered around existing park-n-rides / established transit hubs / light-rail stations, picking up and dropping off “at your door” and connecting to the spokes of the larger system. While definitely more expensive, on a per-rider or per-trip basis, it turns out to be less expensive than running multiple, little-used, low-productivity routes in sprawling suburban areas, trying to effectively serve the same few customers.

The other part of the equation boils down to three major elements, frequency, perceived cost and “the last mile”. The best way to make transit more attractive is to make more frequent. It doesn’t matter if it’s a bus, a train, a boat or a rickshaw, if I can walk out and KNOW that I won’t have to wait more than 5 minutes for something to come by, then transit becomes more attractive. If I have to plan my day, my life, around a schedule where the bus runs every 30 or 60 minutes, then driving, even with all its associated costs, becomes way more attractive.

The perceived cost issue is what one has to dig out of their pocket to ride, today. Monthly passes help hide some of the cost, much like how buying gas for the car rarely gets allocated to each trip taken. Denver’s also been pretty aggressive at having insitutions and employers subsidize monthly pass costs for their employees, many times in lieu of paying for (more) parking. It turns out to be a win-win, with employers / insitutions paying less overall, while their employees / staff / students save money, as well. Metro does a little of this, at places like Wash U, but there are many other opportunities that are being missed.

Finally, “the last mile”. For transit to work for most people, there needs to be a way to get from that last stop on transit to one’s ultimate destination, on at least one end of the trip. Busch Stadium and America’s Center are both close to Metrolink stations. I’m pretty sure that Express Scripts is running their own shuttle buses between the Hanley Metrolink station and their campus. People working or living in downtown St. Louis and downtown Clayton can walk to multiple transit stops. In the suburbs, not so much. In Denver, they’ve concluded that park-n-rides are the best answer in many suburban communities. Concede that people prefer to drive that last mile or three, just get them to stop and switch to transit before they get on the freeway. Let transit take them to dense areas, places where the population justifies frequent service and parking is expensive.

Bottom line, transit will never be the right answer for every trip. Focus on those trips where it can make sense. Make it better, make it attractive, “get it right” and you’ll continue to attract more riders. And to really make it work for St. Louis, we need to move beyond “us versus them”, bus versus rail, and focus on building a comprehensive, effective SYSTEM that moves people to where they want to be!

[…] Steve Patterson at Urban Review STL reported this morning. […]

The quality of urban and architectural design needs to improve significantly before St. Louis can take advantage of any transit, whether it be bus, streetcar, train or even just walking. Cities that are successful with transit systems that all citizens use regularly are comprehensive and effective. They also have an attractive physical environment designed to support those activities.

Technical discussions of transit frequency, routing even use of bus and streetcar can’t have a real impact until it is determined that the design of the physical city and region will actually complement transit.

Whether it is East West Gateway Council, Metro, City Government, County Government or private enterprise that are failing, it is clear St. Louis is far behind in design innovation. In fact implementing basic design principles are rare.

A walking city is essential for a transit city.

Few new projects in recent decades utilize this basic design element, the human being. The result is that St. Louis City population has declined precipitously, barely stabilizing today.

The values of art and civic design are being ignored, and the region of St. Louis is paying the price. Especially the city.

City population has declined precipitously in walkable areas with most of that population moving to non-walkable areas in the suburbs. Loss of walkability is an effect of loss of population, not a cause.

The areas that saw population growth 2000-2010 were the most walkable.

And those areas are? After the loft district, which local area(s) showed the largest growth? And how do you explain the continued population losses in our highly-walkable northern city neighborhoods?

The loft district showed the greatest growth because it started from near zero. The same conclusion can be drawn about parts of St. Charles County (like Cottleville) and parts of the metro east, even though they’re neither walkable nor urban.

Lafayette Square and Old North are the two that come to mind. I think you mean formerly highly walkable nothside neighborhoods. Just like south side neighborhoods they walkability has been destroyed by decades of auto-centric development incorrectly labeled as “progress.”

You and I obviously have different definitions of walkable. Any street or neighborhood with a series of connected, off-street sidewalks and paths is walkable in my book. Heck, the Appalachian and Katy trails are both walkable. I agree, the scenery and the urban fabric has changed, and continues to change, on both the north and south sides of town. That may make the walk less enjoyable, but as long as the connectivity is preserved, so is the walkability.

I guess a parking lot is pretty well the same to you as an attractive row of buildings, both are walkable. You must be one hell of a designer.

No, walkable and attractive are two very different adjectives. Walkable is the physical ability to walk, there is no real aesthetic criteria attached to it. Attractive is an aesthetic judgement, and can also be very non-walkable, especially if there is no sidewalk present.

From Dictionary.com: walk·a·ble

? ?/?w?k?b?l/ Show Spelled[waw-kuh-buhl] adjective

1. capable of being traveled, crossed, or covered by walking: a walkable road; a walkable distance. 2. suited to or adapted for walking: walkable shoes.

You clearly don’t get what the urban environment is about. The Mojave desert is walkable if you have plenty of water. What you are talking about, your definition, has nothing to do with the design of cities. However you would probably fit in well with the second rate minds that brought St. Louis to its current situation.

It is the usual: more excuses, fake arguments, bullshit, unwilling to address real issues, ignoring obvious flaws, don’t care, ignorant of classical city planning methods and so on. This pretty well defines what is going on in St. Louis governance right now and you’d fit right in.

I have never seen an architect with such a disdain for quality design.

No, I’m an architect who values precision in word usage. Walkable does not equal pedestrian-friendly, attractive, urban or even good design. Walkability is an important component of good urban design, but walkability, alone, will not make anything fit into “classic city planning”.

There are parts of our area that are very attractive (Ladue, Wildwood, etc.), but they are neither walkable nor urban. And you’re correct, the Mojave is walkable, but it’s not urban, either. Urban living implies density, and it’s our loss of density that has negatively impacted the pedestrian experience around St. Louis, not any significant loss of pedestrian infrastructure. The sidewalks are still there, there’s just less behind them, just like there are far fewer pedestrians using them.

Yes, absolutely, our autocentric development patterns have negatively impacted the pedestrian experience on most of our commercial streets. People walk less because they drive more. People who drive want parking lots in front of their destinations. Business owners respond by pushing buildings back and putting parking lots, not buildings, next to sidewalks. The sidewalk, at least in the city, is still there, but the pedestrian experience has been degraded. I don’t like it, but it’s the collateral damage that comes with living in a city that continues to lose population. Until we can pry people out of their private vehicles, there’s little the city or designers can do to change this dynamic.

You have it backwards, first I refer you to the land use plan, City of St. Louis 1956, pages 4 and 5 which outlines a city policy of abandoning neighborhood businesses and centralizing them at the expense of walking. Also it is important to note the oil and transportation cartel bought up streetcar lines across the nation and shut them down including St. Louis. Corporate redlining of areas was designed to devalue neighborhoods and encourage abandonment. Meanwhile new development was, and for the most part still is, totally autocentric. The gutting of St. Louis is not an accidental event, and while no doubt some changes would have occurred over the years, the precipitous decline would not have happened without the abandonment of the walking city through government and corporate policies. Read your history, big oil and big corporate interests are the winners in urban sprawl, not the citizens. American citizens are herded around like cattle.

What is interesting here in the discussion of walkability is that many of the areas now deemed walkable were at one time unwalkable..that includes Laf Sq, the loft districts, mid town, etc. Did people make a conscious decision to move into an area to make it walkable? or did they move in (as I would think many did) for the tax credits and other lures first…and then the walkability was a byproduct.

Remember, even the “great” suburbs Webster and Kirkwood and Wildwood were first developed as a place to get away from the pollution, closeness and other issues of urban living. And while the advent of the auto certainly contributed to the decline of cities, there were other issues involved too…like television and now the computer….where people are given no need to walk outside and meet who lives next door to them, never mind the next block over.